By John C. Harris

December 2013

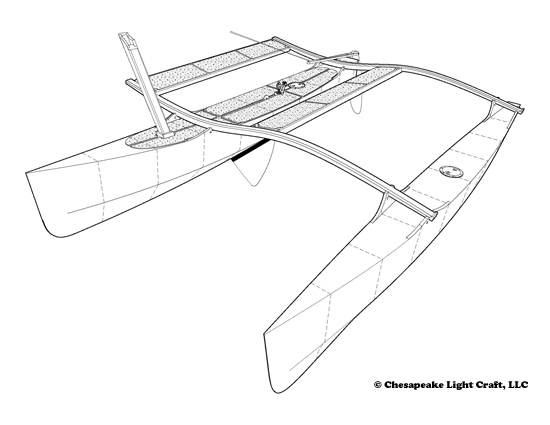

This didn't work out how it was supposed to. The big idea was that this compact and easy-to-build multihull would slip in on the heels of Madness-the-proa, capitalizing on the torrent of interest the big proa generated. The idea was good; for example, sales of our trimaran-conversion rig quadrupled during the Madness media cycle. But we got busy enough that the "mini-Madness" project moved along like molasses running uphill in January, and is only just now ready for sea trials. (Update: view sailing photos here.)

This outrigger design predates the big proa by almost ten years. In 2003, a giant and very well-known national youth program got in touch, looking for a weekend boatbuilding project that would be exciting for kids. A committee was formed, which included some notables from the sailing community. I thought that adolescents were most likely to get excited by something genuinely fast and fun, a boat that would look right with shark's teeth painted on the bow.

The boat needed to be simple enough for unskilled adult-child teams to build, and since really scary numbers were in contemplation---say, a hundred boats the first year---it needed to be cost-effective.

After much discussion a small multihull was agreed upon. This would be a design challenge. Catamarans require a lot of engineering and expensive hardware to support the masts on the forward crossbeam, and there was the issue of a trampoline having to be sewn up. One of the sailors on the committee mentioned the old Malibu Outrigger. This is an intriguing Warren Seaman design from 1950, of plywood, with a big lateen sail. It was much admired and some 2000 were built. The Malibu Outrigger has one big hull, in which the mast is mounted, and a smaller hull like a proa. Unlike a true proa, however, the boat tacks conventionally, with the small hull in the water on one tack and skimming the surface on the other.

(Logic would suggest that a tacking outrigger would be fast on the tack with the outrigger to windward, and slow when it's to leeward. But everyone who's tried a well-proportioned outrigger says that the difference is not pronounced, and if anything might be the reverse of what you think.)

The Malibu Outrigger could only be a starting point for our project, however. For one thing, at 19 feet it was much too large, and the heavy plywood-on-stringer construction was out of the question in terms of cost and difficulty.

I thought the boat would need to be cartoppable, its lightness also making it cheaper because all of the peripheral structures---crossbeams and so on---could be lighter in turn, in a virtuous cycle.

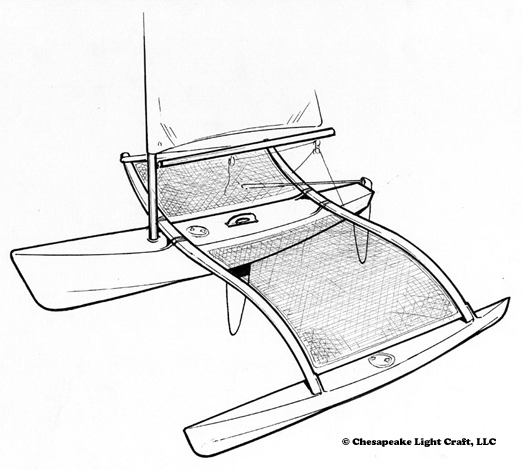

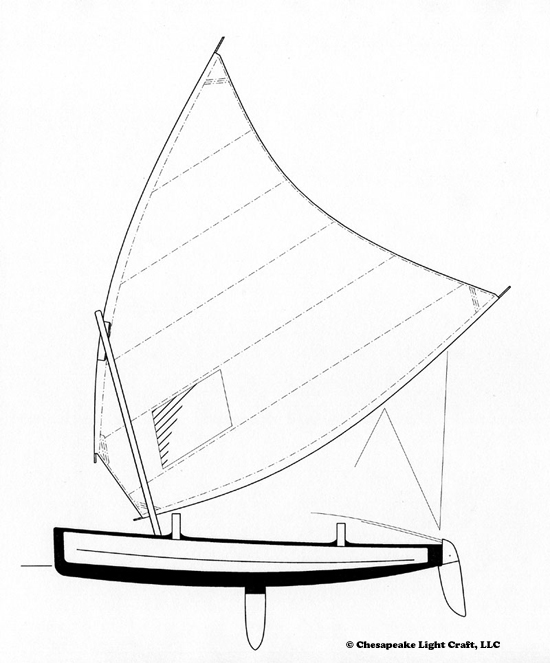

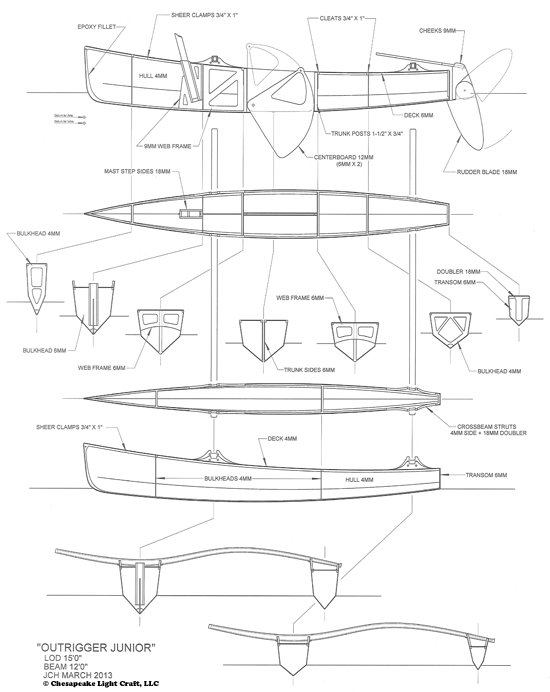

The very first sketch for the Outrigger Junior

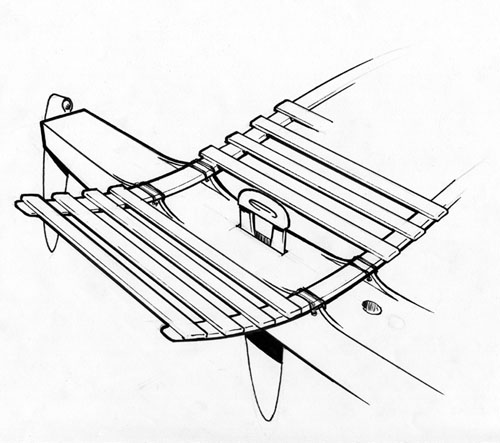

My original drawings have a charming simplicity. Every effort was made to keep the parts-count low, so there was a daggerboard trunk instead of a centerboard trunk. Puzzling over where the crew would sit, I suggested simply lashing some slats between the crossbeams.

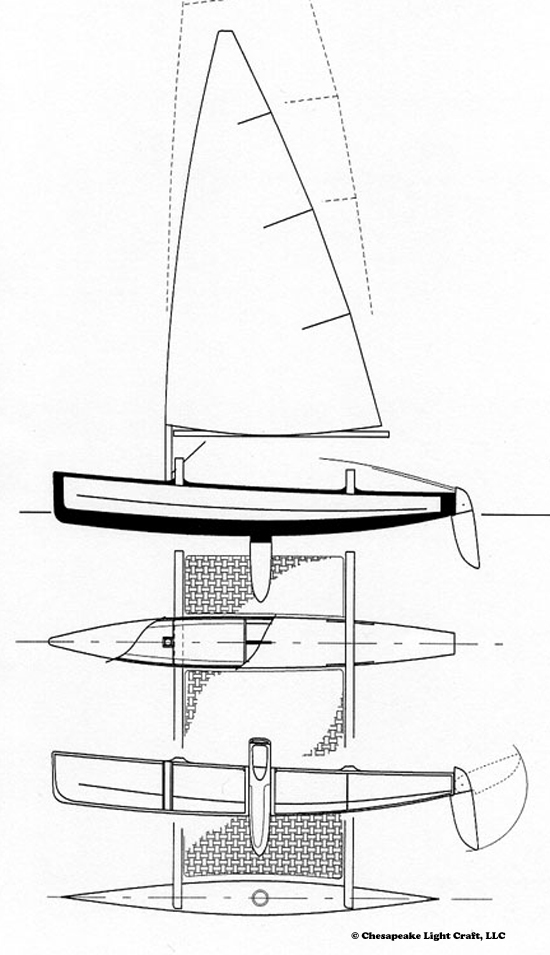

Early sketch of a seating scheme

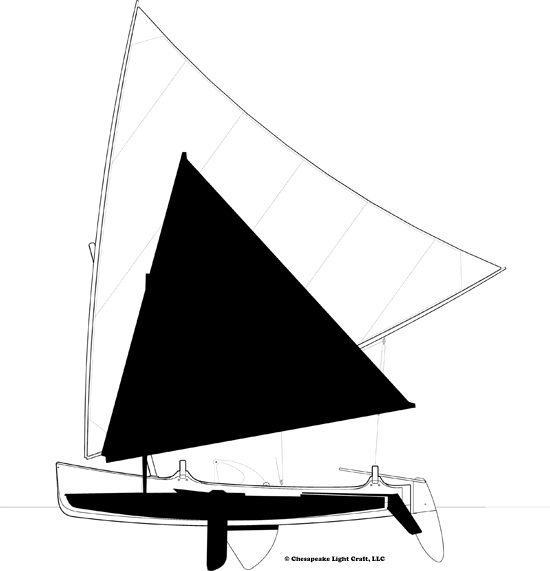

Rigs are the most expensive part of any small boat. My early drawings show a short mast, and some sort of bastard relation of a crab claw sail. CLC's sailmaker revolted at the idea of having to make such large sleeved sails, especially in combination with ultra-bendy spars.

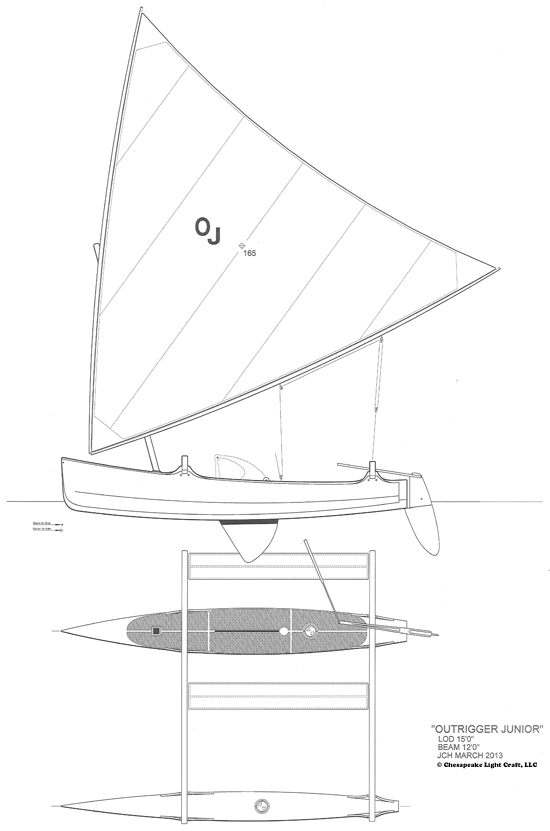

An early rig sketch. The sailmaker said, "No."

An alternate rig reused Laser masts and sails. Anyone who's spent a lot of time in Lasers is welcome to wonder how we'd have made the mast steps strong enough...

As I was puzzling over the details, the initiative seemed to flag at the Big National Youth Program, and our committee eventually dissolved without a single boat being built.

The idea of a really easy-to-build, fast, and transportable multihull stuck around. The original drawings were pinned up in one of the heads here at CLC, and occasionally elicited comment.

Last year I finally felt like I had the time to bring the design to life. With ten years of consideration and study of the drawing on the bathroom wall, I started afresh. A lateen sail of more conventional geometry was chosen. Its rigging is cheap and simple, and the boom and yard straightforward to build. The mast was kept as short as possible. This is why it rakes forward: imagine the mast plumb and it'd need to be much taller than the 12 feet shown.

The crew at the WoodenBoat School, assembling two Outrigger Juniors in July 2013.

return to section:

return to section: