By John C. Harris

By John C. Harris

February 2015

October 2016 Update: Plans are available. Click here for launch photos and plans.

John Guider has covered something like 6000 miles of the Great Loop in a modified Skerry. Marian Buszko piloted his 7'6" Eastport Pram 700 miles around Florida. Scott Mestrezat paddled a stock Kaholo SUP 2400 miles down the Missouri. Various Northeaster Dories have cruised long stretches of every coastline of the US and beyond.

Having designed all four of those boats, I've spent many hours pondering how you might optimize a small, easy-to-build boat just for "beach cruising."

Coastal cruising in tiny boats has always been fringey but it's nothing new. We might date the invention of recreational open-boat voyaging to the publication, in 1866, of John MacGregor's "A Thousand Miles in the Rob Roy Canoe." A gentleman cruising in an 80-pound canoe just for the sport of it must have seemed like pure savagery to the Victorians. The book and its sequels were bestsellers. For a hundred years MacGregor was a primary source of inspiration to people who wanted to cruise in very small boats.

I'm not going to spend a lot of time here selling you on open-boat cruising. Other writers, including MacGregor, will do a better job. Meanwhile, European-style "raid" events are finally, delightfully, becoming popular in the US. More people than ever are overnighting in and out of tiny boats. By mainstream yachting standards this is still aberrant, and probably always will be. I present as evidence a recent Cruising World Magazine review that described a Beneteau 34, with its hot-and-cold running water, as a "pocket cruiser."

Which brings us to my latest personal project, in which I asked myself the question, "Just how small can we go and still have a solid camp-cruiser with good sailing and rowing qualities?" The appeal of these tiny boats includes the low upfront cost, the magical way in which small boats make small voyages feel like big ones, and the ability between adventures to store the boat maintenance-free in the backyard or a corner of the garage. After my last personal project, a cheap little boat that was easy to use and to pack away was an imperative.

The very first priority is the ability to sleep aboard. Such accommodations should be compared not to the usual cruising yacht but to a hiker's bivouac. Just a flat place to lay down, with provision for a tent to keep the rain off, nothing more. The reason this is so important is that very few coastal cruising grounds in the United States afford a place to camp ashore at small-boat-friendly intervals of 15 or 20 miles. The Maine Island Trail is about it; otherwise you're either trespassing or breaking National Park rules.

|

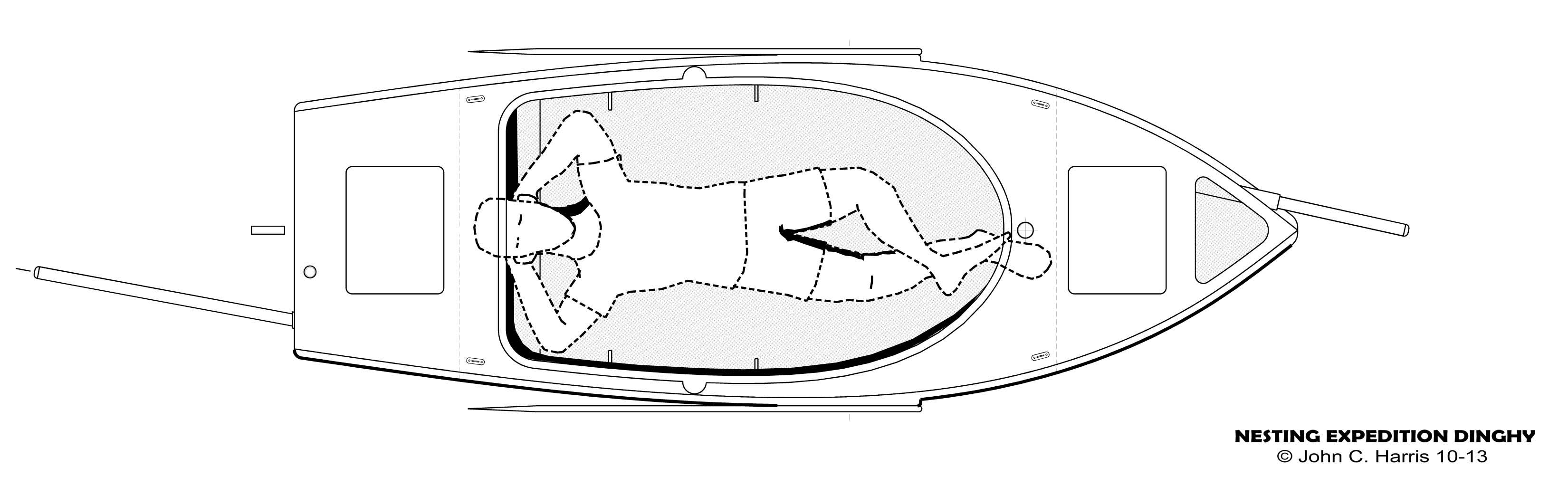

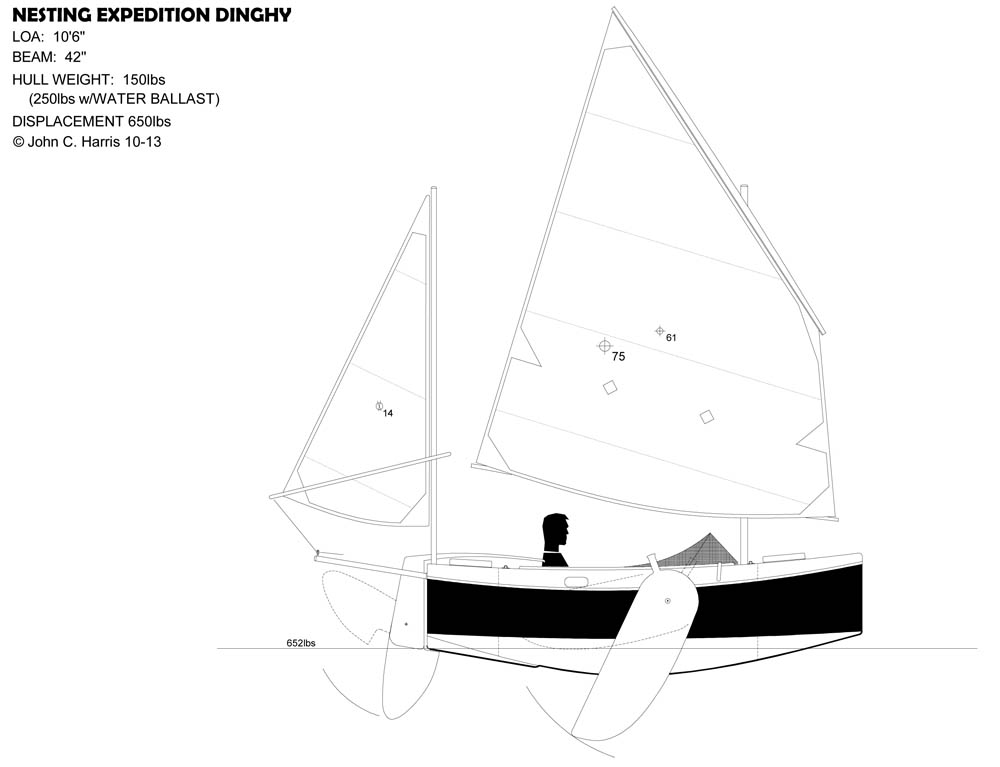

| Room for someone up to 6'2" or so in the nesting version. A non-nesting version gains a few inches of length in the cockpit. |

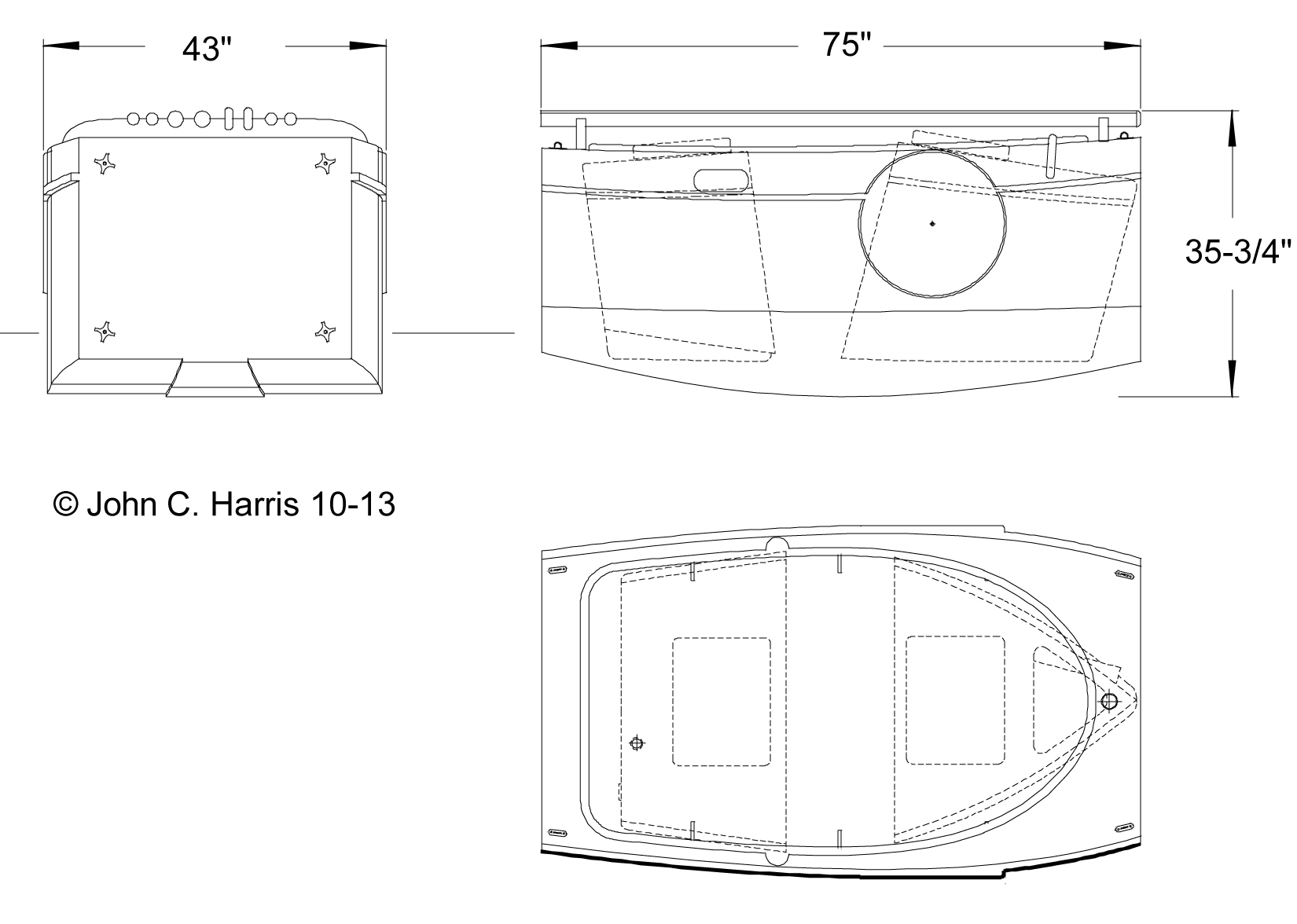

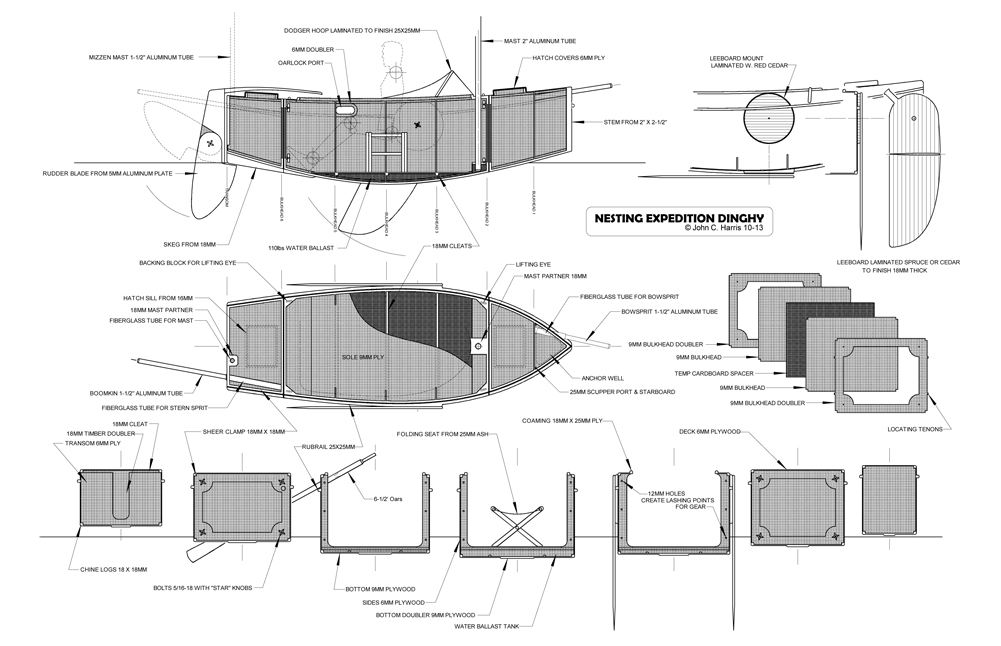

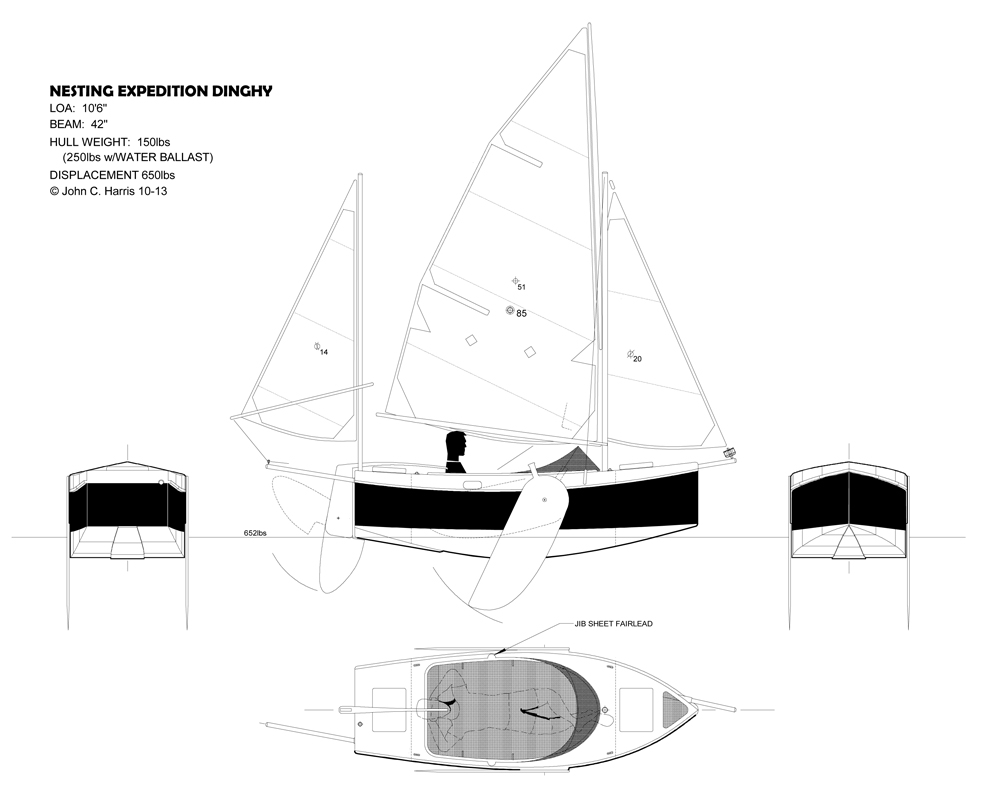

So I started with a 6'3" flat space for sleeping, and added just enough bow and stern for good sailing lines. That brought me to 10'6", microscopic enough to make storage and transport a cinch but with enough waterline to carry a heavy load without digging a hole in the water. To really test the lower bounds of storage space in a long-duration camp-cruiser, I made this a nesting dinghy. The bow and stern unbolt at watertight bulkheads and store in the center section. If the spars are sleeved, in theory everything packs into a 75" x 43" x 36" cube. The whole unit could be stored in an apartment. Or my garden shed. It will fit through a 31-1/2" wide door, and can be transported in the bed of a compact pickup truck. There are distracting daydreams about shipping the Nesting Expedition Dinghy to far-off cruising grounds, like the estuaries of Britain's East Coast, or the River Shannon in Ireland.

|

| How many of these would fit in a shipping container? A fleet cruise in Brittany, anyone? |

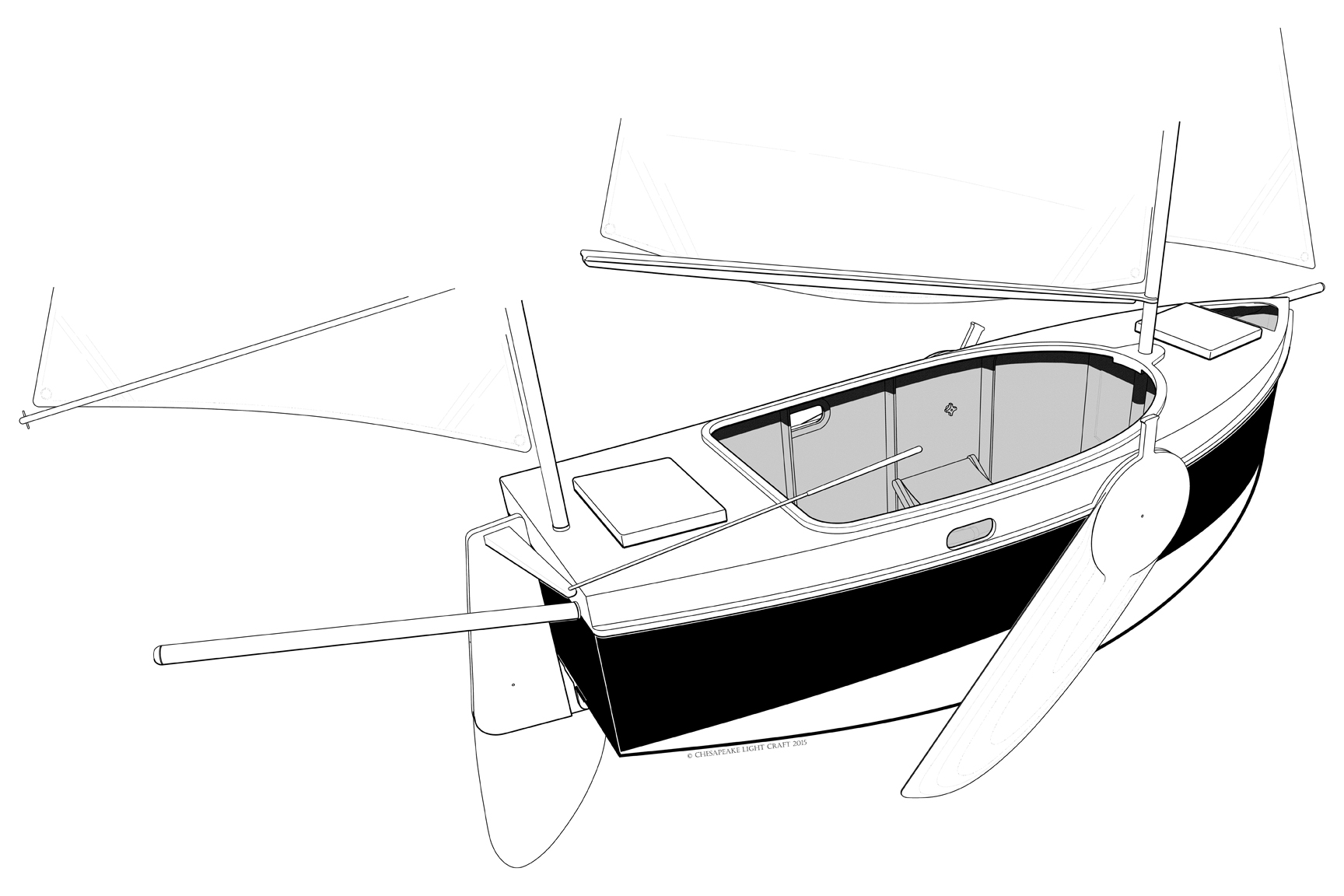

To maximize volume, stability, and performance in a shrunken footprint, the hull assumes the shape of the well-tested "Bolger Box." The sides are dead-plumb; the transom almost square. As it sits in the shop right now, lacking the outwales, leeboard mounts, and the strategic height-reducing paint scheme, the thing looks monolithically wall-sided. I've had to reassure my colleagues that everything will eventually fall into place, with neat proportions and a satisfying look of utilitarian fitness. One is reminded of Mark Twain's remark that Wagner's music isn't as bad as it sounds. N.E.D. (an appropriately gawky name) isn't as ugly as some views suggest. You could get to about the same place functionally with a more traditional hull design, but it wouldn't sail as well and it'd be harder to build. (NanoShip shares a very similar design brief, and with elegant hull lines. But it's larger, will cost twice as much, take twice as long to build, and it doesn't "nest.")

|

| Click for a larger image, or link here for even larger drawings. |

It's worth lingering over the Bolger reference for a quick primer on the advantages of these plumb-sided sharpie hulls. You get strong primary stability. Since the crew will weigh nearly as much as the boat, it's helpful that wherever he or she sits, there's always some bottom beneath them. Flared sides would allow the crew to sit further outboard and "hike out" to resist the heeling force of the big rig. But unless you're on the race course it's easy to forget the downside of that righting moment: sitting there applies the same leverage whether it's balanced by wind force or not. I've seen far more capsizes in boats this size caused by the crew shifting their weight to the wrong place at the wrong moment than by wind action. By pushing the chines out to the same width as the rail, I get maximum righting moment on a given beam and the boat is less sensitive to where the crew is sitting.

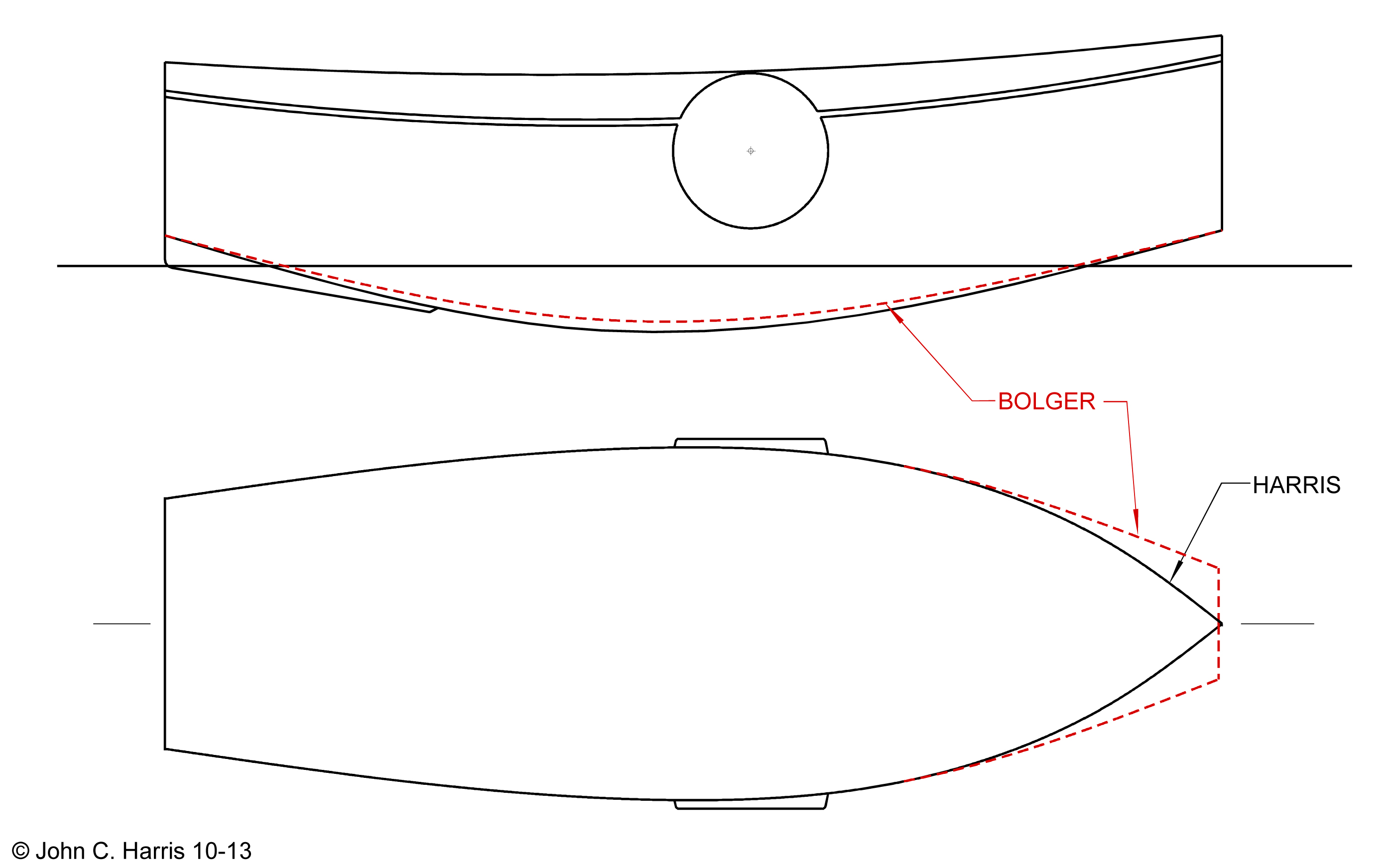

(Bolger would have taken this quite a lot further. He'd have given the boat a square pram bow, maybe 15 inches wide. At a stroke the boat's volume is increased dramatically. So is the waterplane area, so you'd have more stability on the same length and beam, and you could make the hull shallower without losing displacement. With straighter waterlines, the boat is faster in smooth conditions. I owned a Bolger design shaped about as described, and while it sailed amazingly well most of the time, the scow-like flat surfaces at the bow would pound and dig in and sometimes bring you to a halt when sailing upwind in light air and motorboat chop. On the Chesapeake, all sailing is upwind in light air and motorboat chop. Thus I chose a pointy bow for N.E.D. In choppy conditions, a sharpie hull that's actually sharp will be easier to keep going.)

|

| Phil Bolger would have given the boat a pram bow for more volume on the same length and beam. I appreciate what that gains you, but a pointy bow will be better in chop and you'll spend less time on shore explaining why the hell your boat is shaped like that. |

Even without the extra volume afforded by a pram bow, there's still room up forward for one of my favorite beach-cruiser features: a dedicated self-draining well for storing the anchor and its rode. Never will muddy water infringe on the accommodation.

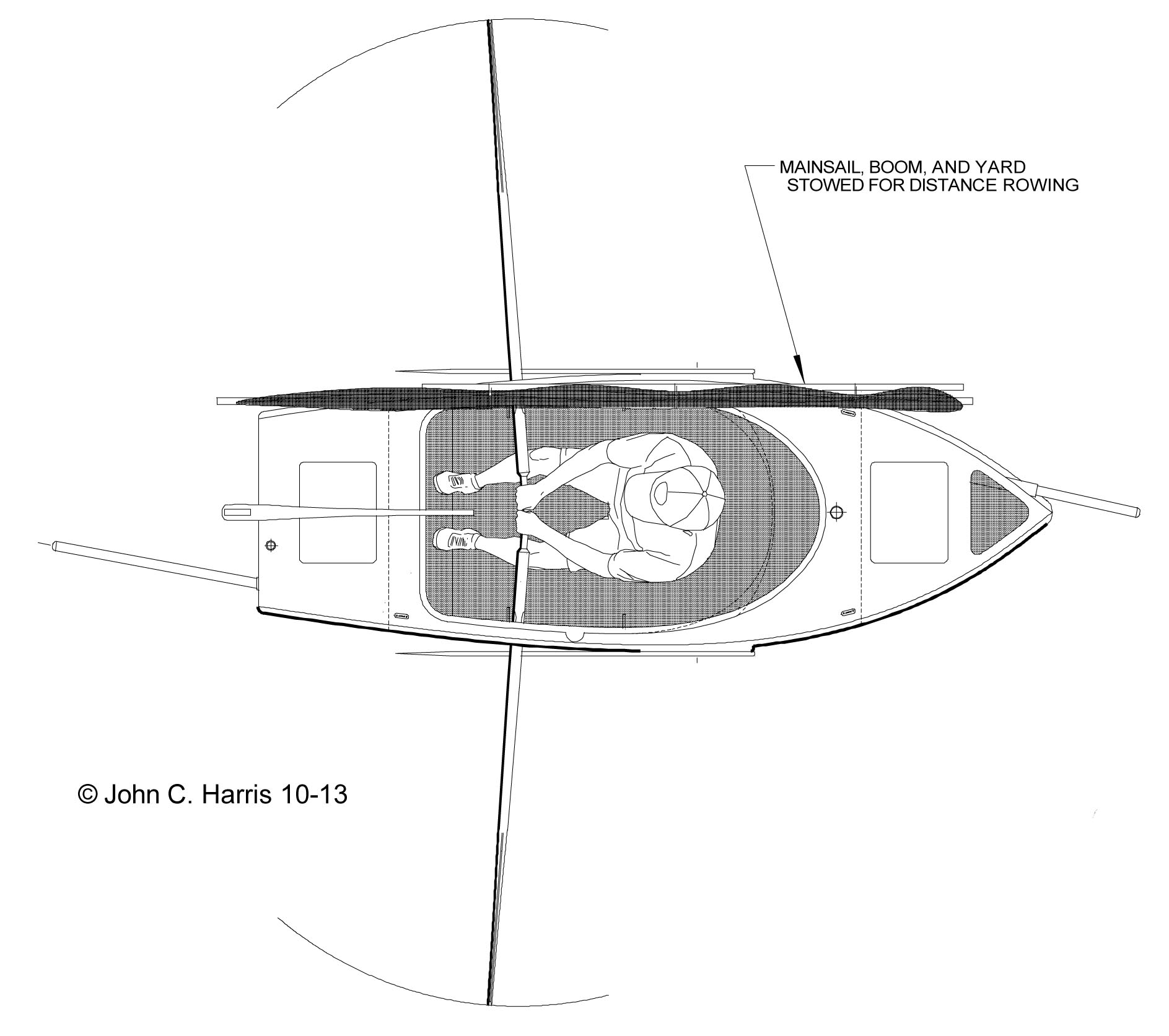

The whole middle of the boat is open space, reserve buoyancy being provided by two large watertight lockers fore and aft. Instead of a thwart, a comfortable rowing stool is nicked from Bolger (who borrowed it from Herreshoff). The seat folds and is stowed out of the way for sailing. The oars are shipped through ports in the side. This is necessary in part because of N.E.D.'s substantial freeboard, but the main reason is that it allows you to strike the mainsail down on deck without fouling the oars. A critical tweak for close-maneuvering, when you need to douse sail and spring to the oars without getting tangled up.

|

| Oars rigged through ports in the side allow the mainsail to be stowed on deck without being in the way of the oarsman. |

This is one of the rare occasions when I set out to make a boat heavy on purpose. With kayak-building techniques and materials, this could be an 80-pound hull. It'd be fragile, and very skittish under sail, however. The only way to make a boat this size forgiving of inattention is to make it quite heavy. Mine is robustly constructed, with a bottom that is 3/4" thick down the center, no fewer than six structural bulkheads, and a heavy fiberglass sheathing. Most prominently, there's a double bottom housing about a hundred pounds of water ballast. Not enough to make this boat emphatically self-righting; you're still going to need to play the mainsheet and mind the puffs. But the water ballast will settle N.E.D. down in puffy conditions and make her more relaxing to sail.

So we end up with a stripped hull weight of around 150 pounds, about as much as a Sunfish. Too much for easy cartopping but still very light for moving around with a dolly or the smallest of trailers. With the hull unbolted for nesting, an ordinary hand truck will serve for shifting the boat in and out of an apartment building's freight elevator or my garden shed.

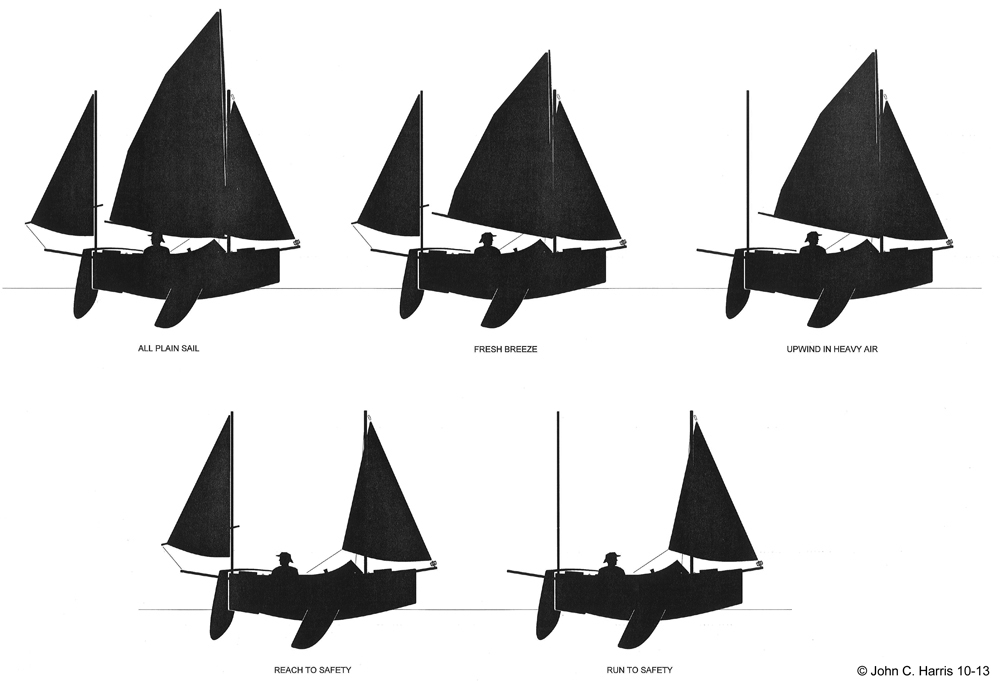

As the boat's not sailing yet, I can offer only educated speculation. While the lug-rigged yawl will appeal to those in windier settings, I specified a fairly large jib-headed rig for the Chesapeake's light airs. It'll be fun to to play with all of those strings. Yet the rig is highly functional, offering at least seven sail combinations that can be configured in seconds to suit conditions. The hull speed is all of 4-1/2 knots. This is moving MUCH faster than someone hiking with a backpack could maintain. And with a payload of 400 pounds of crew and gear, you could carry weeks of supplies. With a little boost from waves, I'm sure the boat will exceed hull speed on a fast reach. The ability to cover 25-30 nautical miles a day opens up vast swathes of beautiful estuary cruising. When the wind dies, you can still cover ground much faster under oars than you could walking on land.

|

| An efficient sailplan of 85 square feet provides plenty of horsepower. The mizzen is great for balance under sail and for holding the boat steady at anchor or while hove to. |

|

|

The yawl rig, with a roller-furling jib and a "Solent lug" mainsail (visually almost |

|

| If you live in windier areas or just want a simpler rig, a balanced lug mainsail and a leg o' mutton mizzen offers a lot fewer strings to pull. |

I'm not a big fan of leeboards. Surface-piercing foils are inefficient, and they need to be physically large to provide the same amount of lift as the usual daggerboard or centerboard. In this case leeboards were a given to create a roomy cockpit. The usual installation is much simpler, with a rope pivot at the rail and water pressure holding the leeboard in place under sail. This is cheap and easy to build, but leeboards rigged that way must be "tacked," just as much work as tacking the jib. I prefer the rigid, cantilevered mount shown here. It's more trouble to build, but this allows you to leave one or both boards down for short-tacking. It may be found in trials that the boat does just as well with a single leeboard.

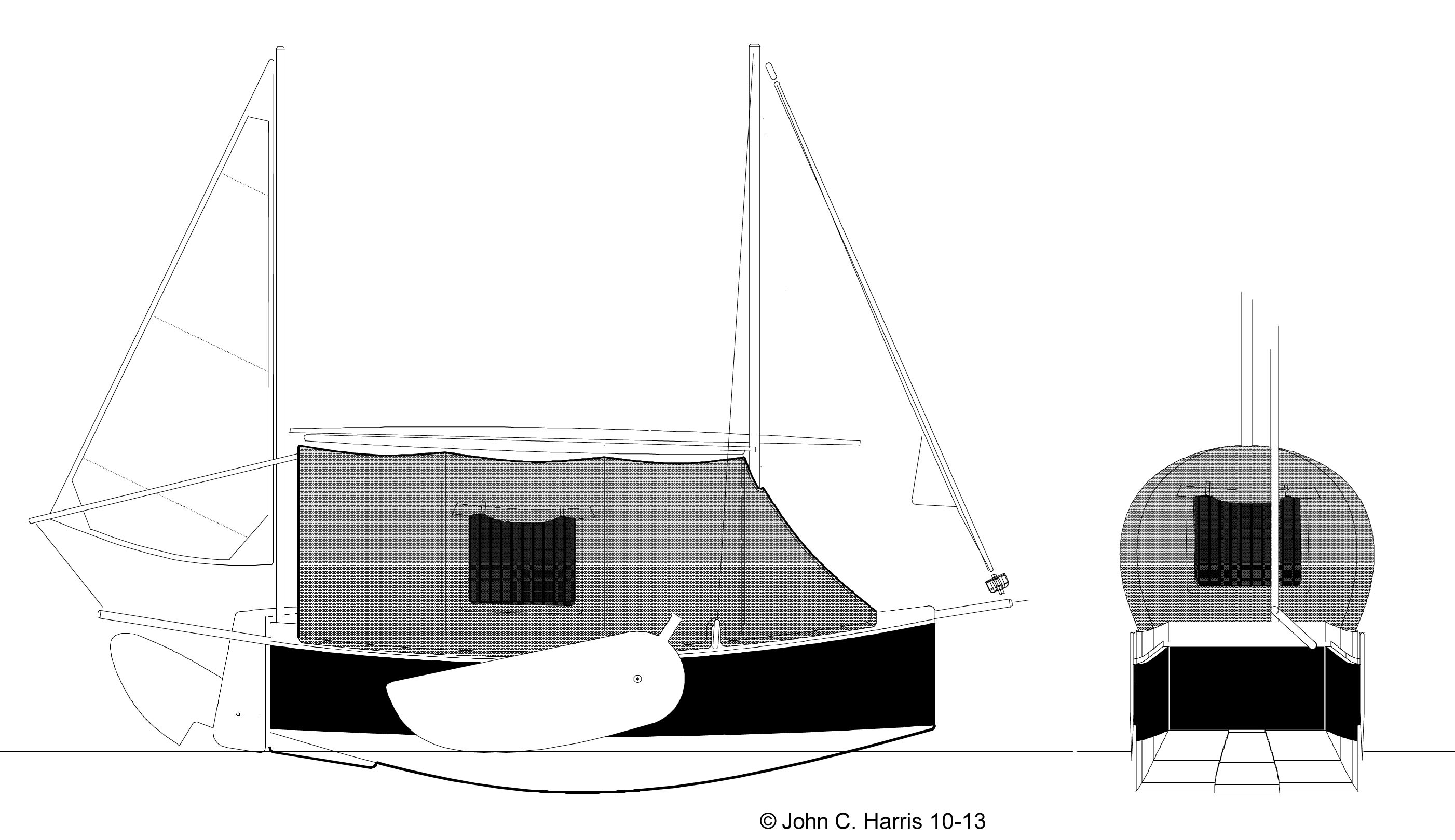

Compared to most small beach-cruising boats I think N.E.D. will be pretty safe when it gets rough, especially in skilled hands. But it's not a keelboat. Deep water crossings would be avoided without the guarantee of good weather. This boat's itinerary will be rivers, lakes, and bays. At the end of the day you'll push far up into the marshes to drop anchor in a few inches of water. The dry and well-rested skipper will lean back to take in the secluded anchorage, the stillness broken only by the sighing of the wind in the reeds. The nylon cockpit tent will be snapped into place and snugged down to keep out the damp and the mosquitos, and the camp stove lit. With no marina bills to pay, between expeditions the skipper worries only about finding time for the next adventure, and dreams idly of building a second hull so that two may cruise in company.

|

| A cockpit tent uses off-the-shelf tent poles and seam-sealed rip-stop nylon. A simpler boom tent made from a tarp would work at a fraction of the effort and expense. |

|

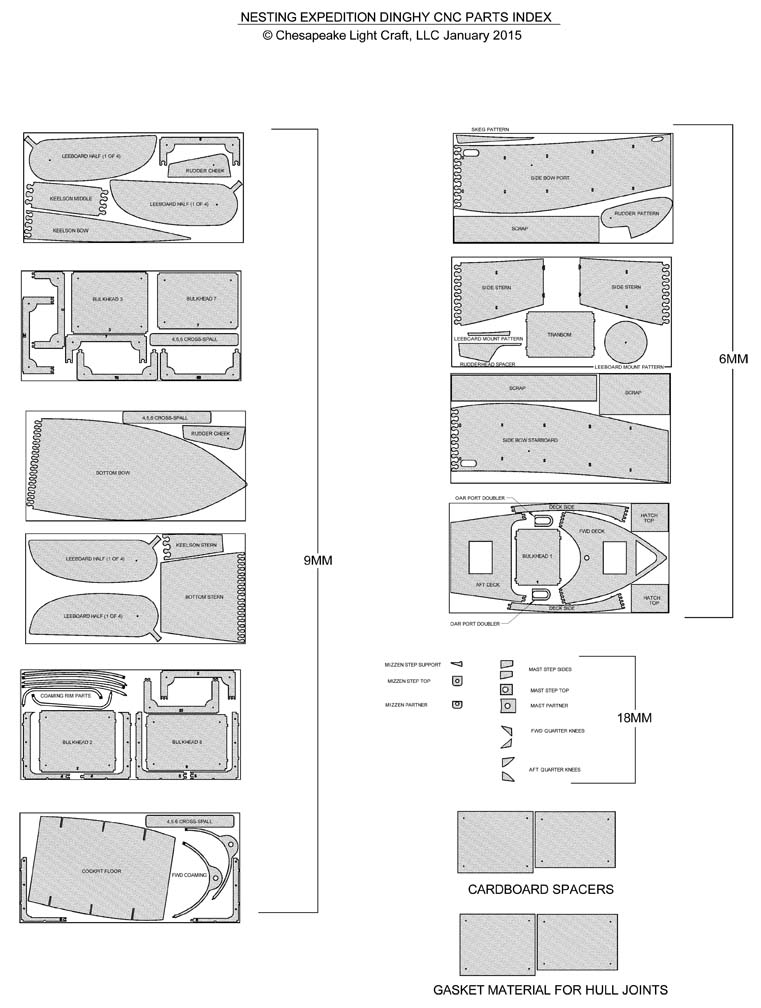

| The kit comprises an impressive heap of plywood. |

|

| Luckily I have a CNC machine for all that cutting. |

|

| Construction begins at CLC by assembing the structural bulkheads. Everything in the boat is prefabricated on the bench, sealed with epoxy, then finish sanded before hull assembly. |

|

| Even the hull panels were pre-finished on the bench before boat is assembled. Chine logs are being glued in here. Using chine logs rather than epoxy fillets is simpler and cheaper in this particular design. |

|

| I did use fillets to secure the bulkheads to the sides and bottoms. Note the take-apart bulkheads, with bolts already in place. The hull will be cut apart at the bulkheads quite late in construction, just before it's time to paint! |

|

| The designer sheathes the bottom in fiberglass. |

|

| With the leeboard mounts and rails in place, the boat's proportions begin to come together nicely. |

Click here for the latest updates on the Nesting Expedition Dinghy.

return to section:

return to section: