Round Table Discussion: The Design of Hard-Chined Home-Built Kayaks

By Eric Schade, Nick Schade, and John C.Harris

November 2015

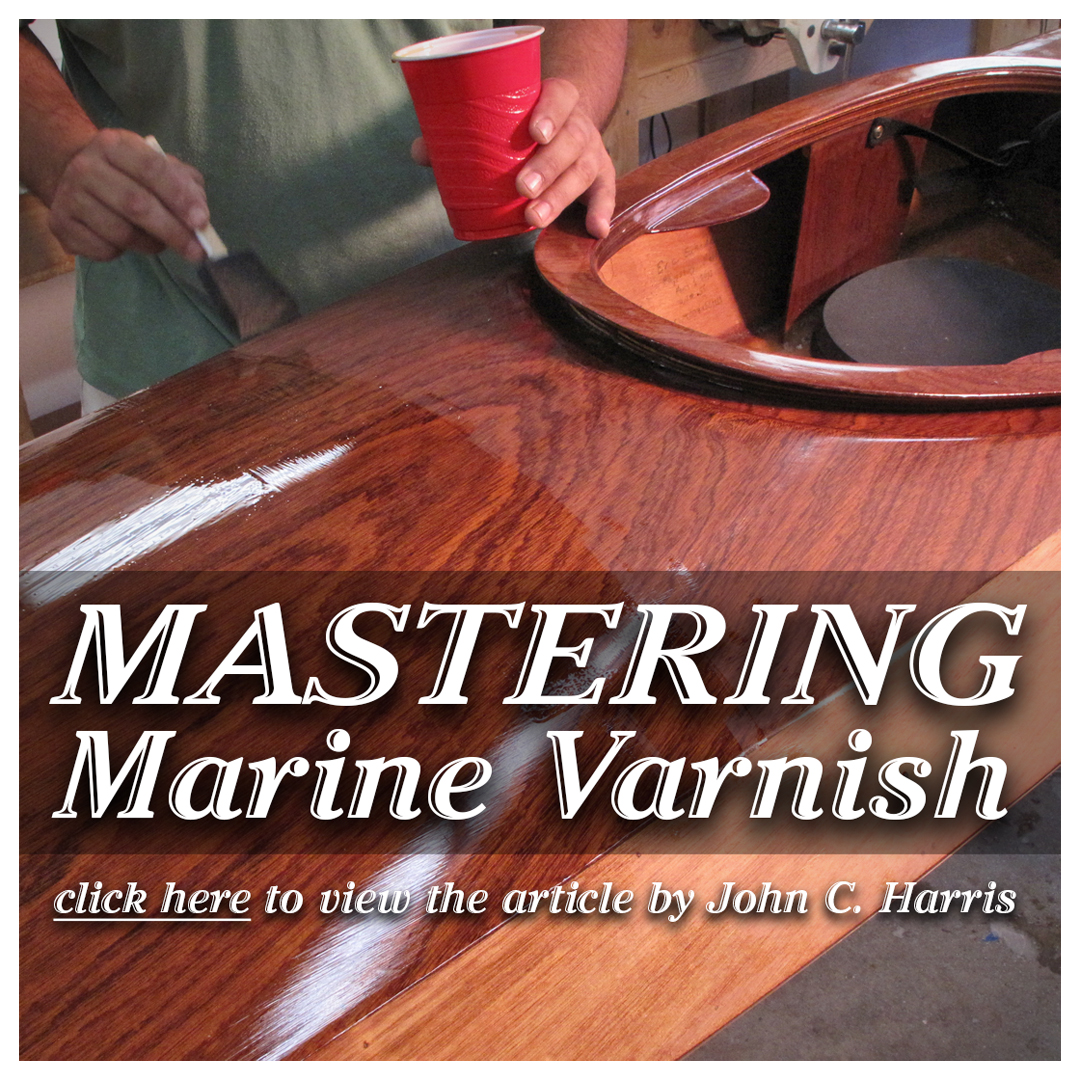

|

| Nick Schade's hard-chined Night Heron SG kayak |

The idea of building your own kayak is very, very old. For indigenous hunters of the far north, from the Aleutians to the east coast of Greenland, building your own kayak was a matter of subsistence and survival. Replicas of the aboriginal kayaks perform incredibly well in every respect. Modern designers stand on the shoulders of giants.

Building your own kayak (or any boat at all) for recreational purposes would have marked you as quite daft until the late 19th century, when the middle class in this country had acquired enough free time to actually recreate. From there the world of amateur boatbuilding took off, and kayaks and canoes were available as kits from the earliest days. I've seen magazine ads from 1906 for build-it-yourself canoes. "Double-paddle canoes," the polite term for the early recreational kayaks, were stodgy performers by today's standards, for the most part.

The phenomenon of the do-it-yourself kayak kit as we know it dates to around 1960. That's when Englishman Ken Littledyke invented "stitch and glue" construction, which involves sticking pre-cut plywood panels together with fiberglass. He put out a series of kayak kits in the 1960's and 1970's under the company name Granta (licensed on this continent to the Canadian company Country Ways). It’s the mark of a true innovator that some of those archaic designs perform as well as the best 21st-century kayaks. People still build some of his kayaks today and every stitch-and-glue kayak descends from Littledyke’s work.

|

| A 1906 ad for build-your-own boat kits. |

For a round-table discussion of the evolution and state of the art of the home-built kayak, we convened Eric Schade of Shearwater Kayaks in Phippsburg, Maine, his brother Nick Schade of Guillemot Kayaks in Groton, Connecticut, and John Harris of Chesapeake Light Craft in Annapolis, Maryland. Between them they have something like a hundred years of experience designing, building, and paddling kayaks. Separately, and especially after the three companies joined forces between 2005 and 2007, these designers are responsible for tens of thousands of amateur-built kayaks all over the world.

Some of this is fairly technical, but if you’ve ever had any curiosity about kayak design, this is a deep dive into the art and science.

Kayak Design Retrospective

By Eric Schade, Nick Schade, and John C. Harris

John Harris: My personal history with home-built kayaks dates to the 1980's. There were scores of designs available back then, but if compelled to speak in generalizations, I would say that there weren't many sophisticated kayak designs you could build at home. Sure, by the 80's there were a handful of excellent high-performance production sea kayaks, but amateur builders could choose from some fairly clunky plywood designs, or a whole bunch of skin-on-frame designs. The majority of the skin-on-frame designs were descended from Klepper- and Folbot-type hulls, not the Inuit designs we use as a touchstone today.

By the 1990's, there were better options for home builders but for a long time it was hard to see through the noise and identify the really good designs. My broad-brush-strokes history of home-built sea kayaks would begin with kayak design being kind of all over the place in the early 1990's. By the late 1990's the designs had grown much more sophisticated, with a marked trend towards long-and-narrow hulls. A lot of boats with less than 22" of beam, that sort of thing. "Narrowboats," as I call them, will always have a hardcore following, but by the early 2000's we could definitely see people finding all kinds of reasons to shift into beamier, more versatile kayaks that require less training and fitness. That trend continues today.

Eric Schade: In the early 1970s, my dad built a kayak kit he ordered from the back of Popular Mechanics or some such publication. The boat was probably 12 feet long, 28" wide, and skinned with rigid fiberglass panels screwed to a wooden frame. The seams were sealed with fiberglass tape and polyester resin. As a teen I was often given use of the kayak and recall fun paddling in waves that were difficult to manage in the family canoe. As a teenager Nick found a fiberglass whitewater kayak which started to come along on these open-water adventures. That turned out to be too slow and had some control issues in ocean paddling. We learned a lot from that.

When Nick and I started designing and building our own kayaks around 1986, we did so to get a good functional kayak capable of working in ocean conditions. Commercially-built sea kayaks as we know them today were barely available. We saw advertisements for them and Nick based his early designs on interpretations of these. It was in fact several years before we saw another sea kayak on the water.

Nick Schade: The kayak our dad built was really a “fuselage frame” style skin-on-frame kit in the vein of a Klepper or Folbot but with a “high tech” skin of fiberglass panel. I remember our dad talking about getting a Folbot kit but he decided it was too expensive and found this kit somehow. For me, this early exposure to kayaks planted the bug, especially since my older brother Eric got dibs on it while I stayed in the family canoe.

What reawakened this bug was reading about the early kayaks that actually rated the designation “sea kayak” in the much-missed Small Boat Journal magazine of the early 1980’s. Dave Getchell Sr., the editor there, started featuring “ocean” or “sea” kayaks in the magazine. Up until this time a “sea kayak” was just any old kayak that was being used on the ocean. The aforementioned Kleppers and Folbots were the most common, but the kayaks discussed in SBJ were fiberglass and designed specifically for rough water, long distance touring, and expeditions.

Eric was looking to upgrade his kayak and I upgraded my CAD to a naval architecture specific application written for America’s Cup boat design. Eric and I worked together to come up with something with a bit of my old whitewater kayak in it but the improved efficiency of a longer, narrower sea kayak. We included rocker, had a fairly flat bottom, and a round sheer like my whitewater kayak, but a swept up bow and stern with a bit of “V” near the ends to promote tracking.

It was a bit tight, especially for someone Eric’s height, but it was fun. By this time we were actually seeing sea kayaks on the water fairly regularly, and Eric and I started visiting the Maine Sea Kayak Symposium in Castine, ME. This led to a longer, narrower, slightly higher version that I tweaked further before making a ‘glass version in a short-lived fantasy of building ‘glass boats.

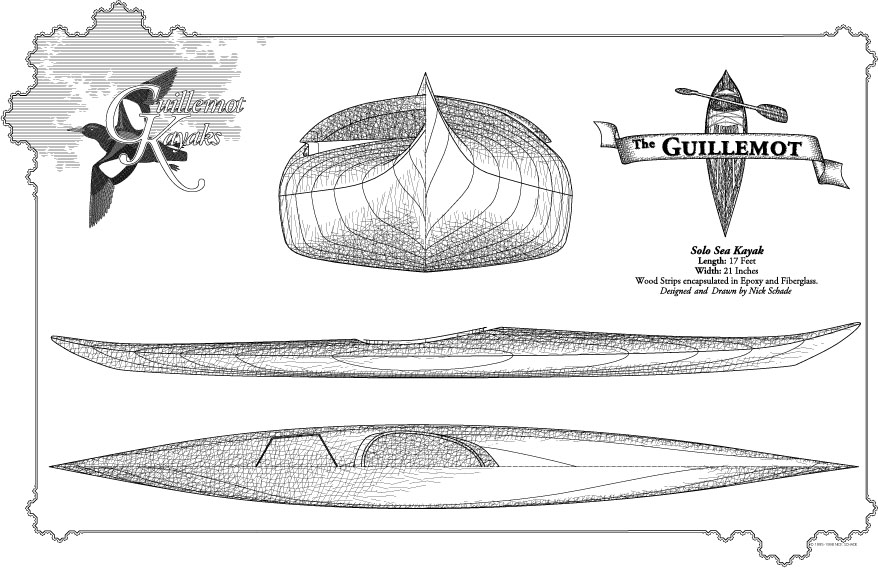

|

| One of Nick Schade's early commercial successes, the strip-planked Guillemot. |

John Harris: My career in kayaks brackets the rise of the World Wide Web and the phenomenon of the bulletin board. And there was a LOT of loud arguing about what made a good home-built kayak in the 1995-2000 period. I was in the middle of it and at the time found the quality of debate pretty low. (It didn’t help that CLC’s kayak offerings from the early 1990’s were neither especially elegant nor paragons of handling. There, I said it. They did get loads better.) From the perspective of 2015, my sense now - as it was in the late 1990's - is that kayak design is a matter of considerable nuance, and you weren't getting much nuance on the bulletin boards. I feel like in 2015, people understand the trade-offs better, and the conversations acknowledge that there are different horses for different courses. So for example, we can have kayaks with lots of rocker that handle great in waves, and the addition of a tracking aid like a skeg is viewed as a practical choice for such boats, not apostasy and evidence of bad design.

Nick Schade: When I first got online there were no bulletin boards. The boatbuilding communities I found online were either listserves or Usenet newsgroups. I believe the first community I found was the newsgroup rec.boats where the topics ranged across all boating-related subjects. Rec.boats.paddle appeared soon where the discussions were generally more relevant to sea kayaking. I was looking for a place to talk about building kayaks, so I helped start the rec.boats.building newsgroup. These were all fairly open forums for a wide range of subjects, but it was a good way to connect with others with similar interests. The more focused groups were listserves, or email mailing lists, such as Baidarka and Paddlewise discussing traditional skin-on-frame kayaks and sea kayaking respectively. Both hosted great discussions about boat design and wandered occasionally into kayak building. The Usenet newsgroups still exist, but are largely spammed into uselessness. Baidarka ended in 2007; Paddlewise continues, but is largely quiet.

With most skills, either in-the-shop or on-the-water, people tend to be fairly conservative. They will find a system that works for them and start to feel that it is the only right way. But, by allowing an open discussion, a lot of ideas get tossed around and the benefits and problems can get aired. While the anonymous nature of online discussions can create hurt feelings, the fact that it needs to be written down defended allows people time to think about the ideas, go out and try them, and then come back and continue the discussion in a way that doesn’t happen while sitting in a bar.

Eric Schade: Nick really was more into the bulletin board scene than I was. I just like to build, experiment and get the feel of what I built.

John Harris: Against this backdrop, how have your designs evolved over the last 20 years?

Nick Schade: In the mid 1990s sea kayaking exploded. Sophisticated British designs were imported, domestic companies took hold, and lots of new designs appeared. Among the fiberglass kayaks there were hard-chined, soft-chined, multi-chined, and round-chined hulls, and more sophisticated rotomolded designs also started appearing.

I was paddling with friends with a variety of different sea kayak designs and it was getting to the point where seeing another sea kayak was not a noteworthy event. Events like kayak symposiums were becoming common and there was a cross-current of idea sharing as the sport of sea kayaking started to mature. My skills on the water improved and my range of paddling areas increased and what I desired in a kayak evolved accordingly. In 1995, after publishing a kayak-building article in Sea Kayaker Magazine, Michael Vermouth, the owner of Newfound Woodwork, was making stripbuilt canoe kits and wanted to expand into kayak kits. He contacted me about adding my design catalog to his selection of kits. This prompted me to start working on my first book, The Strip Built Sea Kayak.

I started a new design on the prompt of a guy in Rhode Island who had a business making carbon fiber boats. He was looking for a kayak to build with his skills. I thought this exotic fiber warranted a sleek, graceful boat that would be fast and responsive. I never heard from the guy again, but "Black Crowned Night Heron" seemed an appropriate name for a carbon fiber kayak. It was a long, narrow design influenced heavily by Inuit kayaks, informed by modern hydrodynamic principles. I wanted a fast boat that could cover distances easily, yet be fun while playing in waves. The Night Heron and its descendents remain really popular designs in my catalog.

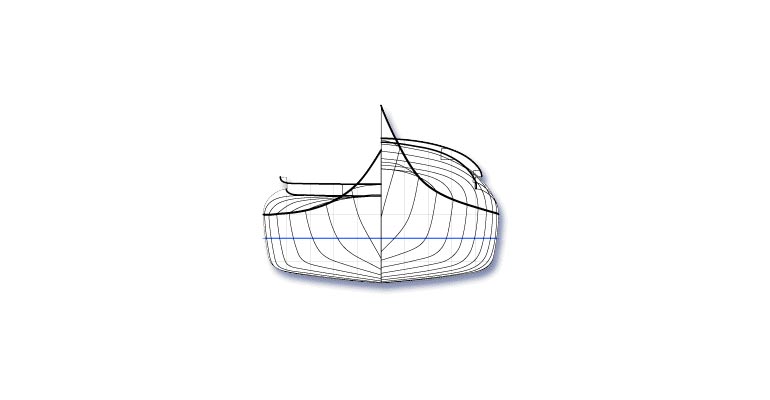

|

| The Night Heron's slippery body plan, showing modest deadrise and flare. |

Eric Schade: The first kayaks Nick and I built were long, wide and stable. Nick had made a symmetrically-hulled 18-foot stripper. I made mine a bit shorter using the same forms. These boats benefited from rudders; we had found them difficult to manage without a tracking aid in some conditions. They were fast and stable, fun in the rough waters of Maine and Long Island Sound.

I experimented with other long and narrow boats including 17- and 19-foot versions, both 21" wide, based on the Aleutian baidarka. The "Baidarka" was a multi-chined stitch-and-glue kayak which quite closely follows the Aleutian design including the distinctive bifurcated bow. It was fast and seaworthy with good tracking, but somewhat tender for the uninitiated paddler. A second long narrow design I called the "Bluefin" was built in 17- and 18-foot lengths, 21" wide. It was multi-chined with rocker, flared sides and a hollow bow. The Bluefin was fast and seaworthy but had a tendency to weathercock a bit, which was cured with a retractable skeg. I feel it to be my most advanced sea kayak hull. However, being multi-chined it was more fiddly to build and the performance improvement was not really sufficient to be worth the effort.

|

| Eric Schade's stitch-and-glue Baidarka. |

John Harris: Ah, multi chines. A lot of intellectual ordinance to be detonated there. Our computers consistently showed about a 3% reduction in wetted surface compared to a hard-chined boat of similar volume, which I agree doesn't seem worth the trouble unless you're racing. The original CLC West River 180 was a multi-chined boat with almost zero rocker and a very fine bow. It was blazing fast, but an animal in waves. We sold a lot of them based on its speed. I did a clean-sheet redesign of that boat around 2003, called the West River 18. It was multi-chined but had firm bilges amidships and plenty of rocker. That really tamed the boat and it became a lot easier to paddle, but won fewer races. It really made me question the value of multi-chined stitch-and-glue boats outside of a racing scenario, where you're desperate for every small advantage.

|

| John Harris's multi-chined West River 18, which was in production from 2002 until 2014. |

Nick Schade: I always felt the arguments about single-chined and multi-chined missed an important point. Kayak design is more involved than choosing a style of chine. The discussion usually centers around which was easier to build or which was more efficient. To me the question of which to go with centers around how the design was intended to be used. For example, my Guillemot and later Night Heron designs were influenced by my experience with whitewater kayaks which were easy to maneuver. This was because the bottom was relatively flat, and as such when I converted the designs to S&G it made sense to have a fairly flat bottom, and a hard chine.

I was trying to design a playful, responsive boat that was also efficient. While I could lower the wetted surface area a bit by introducing another panel to cut the corner off the chine, the difference between the hard-chined S&G design and the slightly more rounded strip-built design was barely noticeable. The single chine best served the overall design goals I was trying to achieve at the time.

When I started working on the Petrel, I was finding the harder chine at the bow of the Night Heron had a tendency to “lock-in” a bit when surfing, and beating out into the wind, the flattish bottom near the bow pounded a bit. To overcome that, I softened the chines at the bow of the Petrel, but I still liked the control edge provided by the sharper transition between bottom and side at the stern, therefore I hardened up the chine behind the cockpit. To achieve this same shape on the S&G version I created a multi-chined section at the front that transitioned to single-chined as it passed the cockpit.

The difference between hard-chined and soft-chined kayaks is often highly exaggerated. People like to say that hard-chined kayaks are more stable, and will compare widely disparate kayaks as examples. Any differences in performance are usually better explained by a whole range of very different design attributes, where the chine shape is only one, relatively minor, characteristic of the overall design.

A more rounded shape, achievable with more panels, to better approximate a curve can reduce the wetted surface area which is certainly important, but there are other factors such as width and length that are larger factors. Designing a racing kayak, or surfski I go for a rounded bottom, approximated in S&G by multiple chines, but for a slower, cruising design I may just go for a shorter length. Personally, I don’t think going from point to point with a minimum of effort is all there is to sea kayaking. Creating a design that is fun to paddle requires balancing a variety of compromises into an integrated kayak. Focusing on just the chine misses the point.

Eric Schade: My first S&G boats were also hard-chined boats. They performed well both for straight running and for turning and maneuvering.

My experiments with the Aleutian baidarka-styled boats were interesting and made nice boats which were fast and tracked well in all conditions. They were not easily turned; they carved a large radius turn, and wind and waves had little effect. The sharp entry and "skeg" aft helped keep them on track. The flaring upper panels of the bow helped keep the bow up though the low profile made them wet in chop. The elliptical multi-chine section of the hull probably added some speed and certainly make a graceful looking hull. One difficulty with the eight-panel hull was in construction. They required high precision in cutting the panels in order to get a fair hull. Some of my early scratch-built multi-chined boats have some dips and bumps. CNC machines later solved that problem.

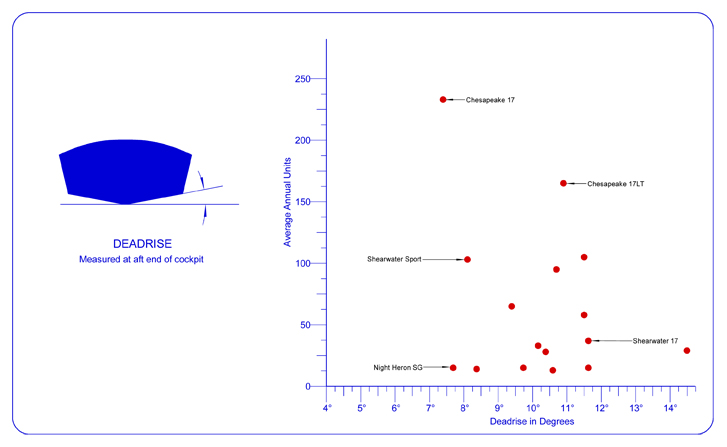

John Harris: For the sake of discussion, I pulled sales numbers on 14,703 hard-chined CLC kayaks (!) sold over the last 15 years and graphed the results. I limited the study to narrower, traditional sea kayaks, leaving out rec kayaks like the Wood Ducks and Mill Creeks, as well as our various multi-chined offerings. Aside from length and beam, the three categories in the comparison - deadrise, flare, and rocker - probably do more than anything to determine handling qualities.

First up, deadrise:

|

| "Deadrise" is the nautical term-of-art for the V-shape in the bottom of a hull. |

John Harris: My idol Phil Bolger wrote that the only reason for deadrise was to get ballast lower in a hull on a given freeboard. A kayak needs a low center of gravity more than just about any other type and you really do feel more stability if you can sit lower in the boat. Steeper deadrise, however, can make the kayak really hard to turn, and the data suggest a happy medium somewhere between 7.5 and 11.5 degrees. On the other hand, flatter mid-sections have noticeably less wetted surface and are easier to maneuver, which is probably why you never see a racing kayak with a deep-V hull. Over the years I've tried to divine some sort of consensus on the role of deadrise in sea kayak design but have never heard anything definitive. One expert paddler told me that keeping a constant deadrise angle for as much of the underbody as possible was desirable. In a stitch-and-glue boat I'm not sure how that's even possible, and from a naval architecture point of view it's hard to understand how that’d be a virtue at kayak speeds.

Nick Schade: I started designing kayaks out of a desire to have myself a nice kayak. I didn’t study the history of boat design before setting pencil to paper. As such, I didn’t think in terms of “deadrise”. When I first heard the word, it didn’t make much sense to me. I honestly don’t know the derivation of the word, but it has the sound of a word that refers to some aspect of how a traditional plank-on-frame boat was built. As such it doesn’t correspond well in my mind to how a kayak functions. I tend to think of “V”, the shallow “V” of “low deadrise” is fairly flat, and a deep “V” is more deadrise.

I took a step towards shallow “V” when I started thinking about how I liked aspects of my whitewater kayak performance. I was coming from my earlier designs which didn’t turn easily and was looking for a more responsive shape. Around this time I had actually started to experience other kayak designs and decided the stiff tracking of the highly respected early Nordkapp was the exact opposite of what I was looking for.

The ability to change course quickly implies a shallow bow and stern and fairly flat sectional shape with little “V”. Much like whitewater kayaks, the resulting designs have a tendency to “skid out” after initiating a turn. The stern breaks free and quickly slides sideways. This amplifies a small steering stroke into a quick turn.

It also can transform a slight weathercock into a severe course correction. Such “looseness” benefits a paddler who is paying attention to the subtle interaction between the kayak and the water, but an inexperienced kayaker may feel they are riding a headstrong horse with its own sense of direction.

A further downside to underbodies with shallow V is a hard slap as the bow impacts the water after climbing over a wave. The pounding slows the boat down, sends spray flying and is generally distracting. Increasing the deadrise creates a sharper entry as the bow falls back to the water. The “V” bottom hits the water more gradually, slicing instead of pounding.

I prefer a boat that is easy to turn rather than one with stiff tracking. A kayak that is hard to knock off course is also one that is hard to turn back on course. Since the reality on the water is that wind and waves will knock a kayak off course, I prefer a boat that turns back on the desired bearing easily. The goal is to find a happy compromise in deadrise that allows a quick response to turning strokes while maintaining a smooth, gentle, efficient action working through waves. This is accomplished through the interaction of the bottom sectional shape and the profile (or rocker).

Eric Schade: My stitch and glue boats have moderate deadrise for these reasons:

1. Deadrise offers more lateral resistance to wind and waves than a flat bottom would, all other factors being equal. I have found that flat-bottomed canoes take quite a bit of effort to keep on course in a cross-wind.

2. Structurally the deadrise creates a more rigid bottom, more resistant to both hydrodynamic forces, which can flex a hull noticeably, and of course when hitting rocks or logs or dragging up a beach.

3. Moderate deadrise requires less precision in cutting and shaping the hull panels. Small errors tend to be amplified when panels meet at a shallow angle compared to a deeper V. Again this is more of an issue with scratch- built boats than kits.

|

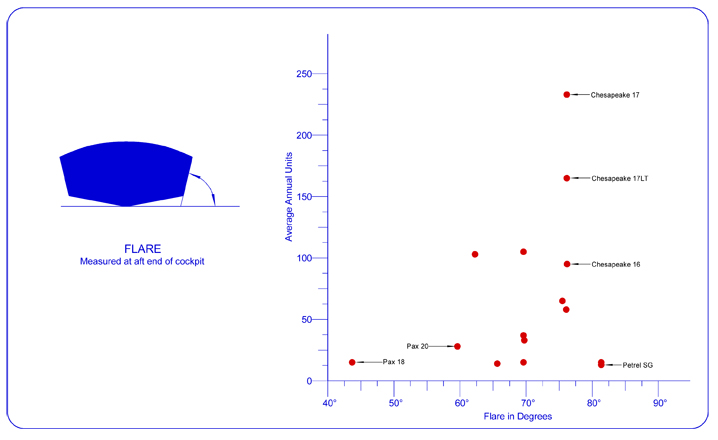

| Here's how our fleet sorts out with side flare. "Flare" refers to the angle of the sides of a boat. |

John Harris: When it comes to the “flare” in the sides of a hard-chined sea kayak, the field shows more variability, ranging from 44.1 degrees in the Pax 18 to 82.7 degrees in the Night Heron SG, with an average of around 75 degrees. More flare equals more secondary stability. Even among indigenous kayak types there is a lot of difference. Some West Greenland Inuit kayaks have nearly plumb sides like the Night Heron SG, while East Greenland kayaks have a huge amount of flare. A lot of Aleut baidarkas featured pronounced flare as well. I've always thought that lots of flare was a good way to combine a suite of desirable qualities: a narrow waterline for speed, plenty of beam for secondary stability, and more stability as the kayak is loaded down. The Pax 18, which I designed for my personal use, was an experiment down those lines. I think the Night Heron SG's plumb sides contribute to its nimble (if challenging) handling, while the Pax 18's striking flare allowed it to fit into ACA racing rules with a super-skinny waterline beam.

Nick Schade: Initial stability is largely a function of waterline width. More width = more stable. Secondary stability is a perception of how the stability changes as the boat is tipped more. If the relative stability increases, people will feel the secondary stability is “high”, where if the relative stability drops quickly people will feel the secondary stability is low. This feeling of stability is a function of how the sectional volume of the boat enters the water as the kayak tips.

Flare, increased width above the level waterline, results in the buoyancy on the tipping side increasing quickly, while simultaneously decreasing quickly away from the lean. This increased volume serves to catch the paddler, providing support and stability.

A boat with a lot of secondary stability can be very reassuring, but often novice paddlers never get beyond the initial stability range before feeling uneasy. A really narrow waterline with low initial stability will feel twitchy and cranky even if the secondary is sufficient to support the clumsiest paddler.

Too much secondary stability can also create situation where the kayak may feel like it “trips” after tipping too far. The secondary can be very supportive until suddenly it quickly drops away to nothing. The paddler leaning into this secondary may be dunked without ceremony when they really test the stability.

Designing a kayak requires juggling many characteristics. While the novice paddler may be most interested in not capsizing, as they get more experienced, they start to think about efficiency, maneuverability, paddling comfort, etc.

With a design like the Night Heron I was looking for a fast, efficient design that was easy to paddle. A narrow 20” waterline is a good start for efficiency, but lacks some stability. By keeping the boat “full” in plan view – sides closer to parallel, rather than pinched at the ends – it is possible to maintain more stability without making the boat too wide.

Keeping the boat narrow at the catch of the forward stroke is more comfortable than dipping the paddle in at a wider point. With a narrow waterline and a desire for a narrow catch, there is not much room for flare. So, a design like the Night Heron ends up with a waterline width nearly the same as the overall width, in other words with very little flare. The result is high stability for the overall width and a fairly smooth stability curve that doesn’t have many surprises.

Flare doesn’t impart handling characteristics in isolation. Flare works in concert with the shape of the chine. A hard chine will serve as a control edge for the kayak. This control edge is deployed by leaning the boat. A little edging on one side will sink the chine into the water while lifting the other, with a resulting change in underwater shape that can be used to steer the kayak. The prominence of the chine is really a function of the angle between the bottom of the boat and the side of the boat. A design with zero deadrise (flat bottom) and slab sides (zero flare) will have a 90° angle at the chine. Lots of deadrise and lots of flare will reduce the significance of the chine. Thus the ability to incorporate the chine shape as a tool to control the boat depends on balancing the deadrise and flare with the need for stability and efficiency.

Eric Schade: I have been a fan of plenty of flare on the hull sides. For a given stability the boats are narrower at the waterline, thus faster and more controllable. As boats with flare are leaned, comforting secondary stability comes into play so that leaned turns feel safe and easy. I find the boats Eskimo-roll well and don't have a tendency to just keep rolling and dunk you again after you get yourself upright.

The top panel on my multi chine hulls tends to be fairly vertical amidships partly because I am looking for something a little different performance wise (for example narrower overall hull) and partly because the above effects can be regained to some extent through flare at the ends and the lower panels are certainly flared.

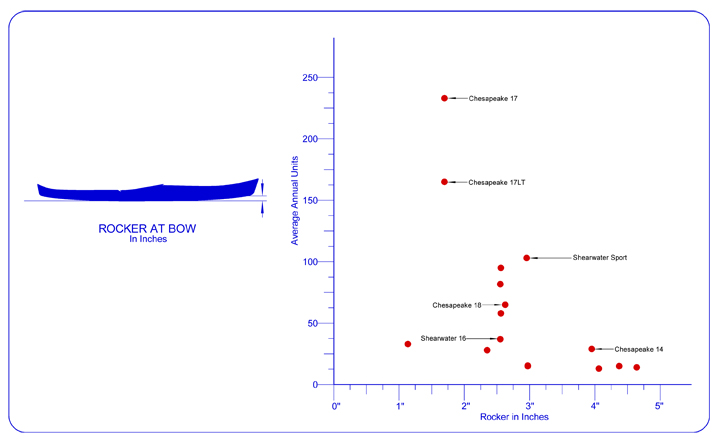

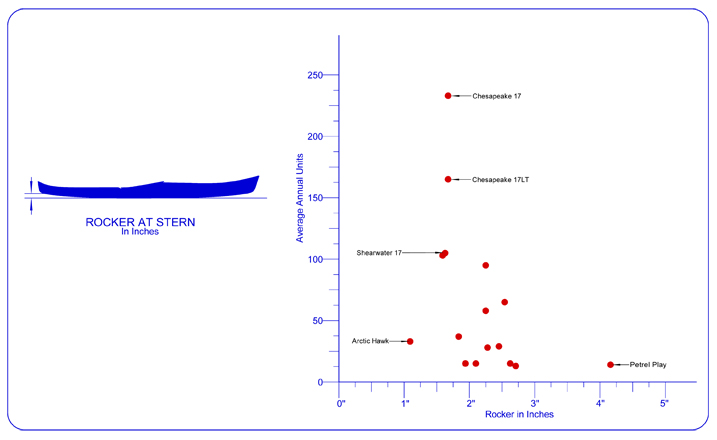

John Harris: Here are graphs showing bow and stern rocker in our sample fleet:

|

| Rocker measured at the bow, just behind the "knuckle" where the keel turns upwards towards the stem. All boats in the data set were scaled to a uniform 17 feet long for easier comparison. |

|

| Rocker measured at the stern, just forward of the "knuckle" where the keel turns upwards towards. All boats in the data set were scaled to a uniform 17 feet long for easier comparison. |

John Harris: Rocker is just what it sounds like; if you place the kayak on flat ground, it’s a measure of how much the boat will rock from bow to stern. Rocker in kayaks was something that's lodged in my memory as a topic that could lead to globe-scouring wars on the bulletin boards in the old days. I was a vocal advocate for more rocker in kayaks because the boats just handle better. It lowers wetted surface AND makes the kayak easier to manage in waves. But a kayak with a lot of rocker simply won't track as well in some conditions, so you need a skeg or a rudder. It's a trade-off I was happy to live with, but there was a cohort who argued passionately that the need for a tracking aid was evidence of careless design. I know that 15 years ago we felt a lot of pressure to design kayaks with less rocker, but I was never very happy with the result. The boats tended to be cranky and wet in waves. The analysis shows a strong consensus around 2-1/2" at the bow and 2" at the stern, whereas if I drew a sea kayak tomorrow it'd have 3" or 4" of rocker. And a nice retractable skeg. (Note that the boats in the analysis were all regularized to 17 feet long to help tease out some patterns in the rather scatter-shot data.) Look through the Smithsonian’s collection of Inuit and Aleut kayaks. They all have plenty of rocker.

Eric Schade: Rocker is a tradeoff between maneuverability and tracking. In a sea kayak, I want to be able to point the bow where I want when I want. Thus I need enough maneuverability to steer and enough tracking so that I am not spending all my effort on corrective strokes. My kayak designs like the Shearwater series tend to be cruising and exploration boats, rather than surfing and playing boats like Nick's. They have less rocker aft than Nick's, thus they have less need for a skeg or rudder for tracking. This is really based on our styles of paddling and where we enjoy going in our boats. Certainly Nick's boats are no slouches at touring and exploring, or mine at playing and surfing, but that is probably the main difference in our design goals.

Nick Schade: I’ve had a hard time with the term “rocker” for awhile. How rocker is measured is confusing. It seems to be a measurement of the difference in height from where the bow (or stern) enters the water and the bottom of the boat. IE, it is a measurement of the distance from the waterline to the baseline of the kayak. Some may try to measure from the knuckle of the stem to the baseline, but I’ve never found a consistent way to measure it. I prefer the Lateral Plane Coefficient as a standard way to measure how much different the keel line is from a perfectly straight line.

The idea of rocker is pretty straightforward. If there is less area to resist turning out near the ends of the boat, the boat will be easier to turn. A small amount of change near the ends can make a significant difference. A skeg is just a tab of surface area that the paddler can deploy near the stern of the boat that will slow down the ability of the boat to turn, like the feathers on an arrow.

Again, I find it easier to turn a loose-tracking boat back on course than it is to return a stiff tracking boat to the desired heading. By properly balancing the “rocker” at each end, it is possible to make a loose-tracking design that is not significantly more likely to drift off course than a stiff-tracking design.

From there it is a matter of looking at the other design factors effecting the performance. For example a flat bottom “low deadrise” design is typically easier to turn than a deep “V”. With less deadrise, the maneuverability is still possible with low rocker. With a deeper “V”, lots of rocker will provide good maneuverability. This all also interacts with stability through draft. A deep draft creates a lower center of gravity which increases stability. Increasing deadrise raises the lowest point on the seat, raising the center of gravity and decreasing stability. Increasing flare may result in a narrow waterline which decreases initial stability while offering a more distinctively supporting secondary stability. Increasing the chine angle to provide a control surface, increases maneuverability, while potentially increasing the pounding going over waves, reducing efficiency. It is all enough to make the head spin.

You can’t change just one thing, hoping to improve just one aspect of performance because rocker, deadrise, flare and chines are all linked in several ways. Changing one affects stability, maneuverability, efficiency and comfort all at once.

In none of this have I mentioned aesthetics. Kayaking is an aesthetic experience. What the kayak looks like matters, not only because things that look better often do actually perform better, but because we are building a kayak and going out on the water because it is a beautiful thing to do. We want to be in a beautiful object when doing a beautiful thing. Balancing all the ugly-sounding design characteristics such as deadrise and rocker into a graceful, elegant, beautiful vessel is what kayak design is all about.

|

| Nick Schade's Petrel Play stitch-and-glue kayak doing its thing, and looking great. |

return to section:

return to section: