One big hull, one little hull. Lots of speed, not much money.

Madness is a lightweight “Pacific” or windward proa, intended for fast cruising with two adults or daysailing with four. With a payload of just under 1000lbs, accommodations are ideal for an adventurous couple who want to cover a lot of ground, island-hopping through the Caribbean or up the coast.

The design brief was for an elegant, inexpensive, and relatively easy-to-build multihull for fast cruising on the Chesapeake and in the Bahamas. Much care was taken to minimize exotic, difficult-to-use materials like carbon fiber and the hope is that this design is more accessible to the home builder than anything capable of the same speeds.

Madness was inspired by, and designed in direct consultation with, proa guru Russell Brown. The design is a fusion of Brown's 30-foot plywood Jzero design from the 1970’s, his more-refined cold molded 36-footer Jzerro, from 1993, and with the proa Mbuli, which John C. Harris designed and built in 2000.

More design discussion, construction photos, and commentary were posted on our blog, here, here, here, here, and finally on the water here. A wrap-up of the whole project is here.

A video discussing the design is here. Some video of the boat under sail is here.

Sea trials in the fall of 2011 and throughout 2012 far exceeded expectations. Madness is fast, perfectly balanced, docile to handle, and strong.

As of this writing (April 2012) we have shipped five kits to courageous "early adopters." The quality of feedback has been very encouraging, and we have now released a comprehensive plans package.

The "kit" comprises all of the boat's plywood components (35 sheets' worth), CNC-cut and packed on a pallet, plus CNC-cut patterns for other components like rudders. Other packages add in solid timber, epoxy, and sheathing materials including fiberglass and carbon fiber.

Specifications

|

Main Hull:

LOA: 30’8”

LWL: 29’3”

Beam: 28-1/2”

Beam, overall: 8’3”

Displacement: 1989lbs

Moment to Trim One Inch: 274lbs

cP: 0.60

|

Ama:

LOA: 22’5”

Beam: 21-1/2”

Displacement, normal sailing lines:

387lbs

Displacement, immersed to deck:

2,029lbs

Moment to trim One Inch: 79lbs

cP: 0.60

|

The Whole Lashup:

Beam between centers:14’5”

Beam overall: 20’0”

Sail Area:

364sq.ft. (Racing)

294sq.ft.(Cruising)

SA/D: 36.43

Draft, boards up: 17”

Draft, boards down: 42-1/2”

|

The Proa Rationale

By John C. Harris

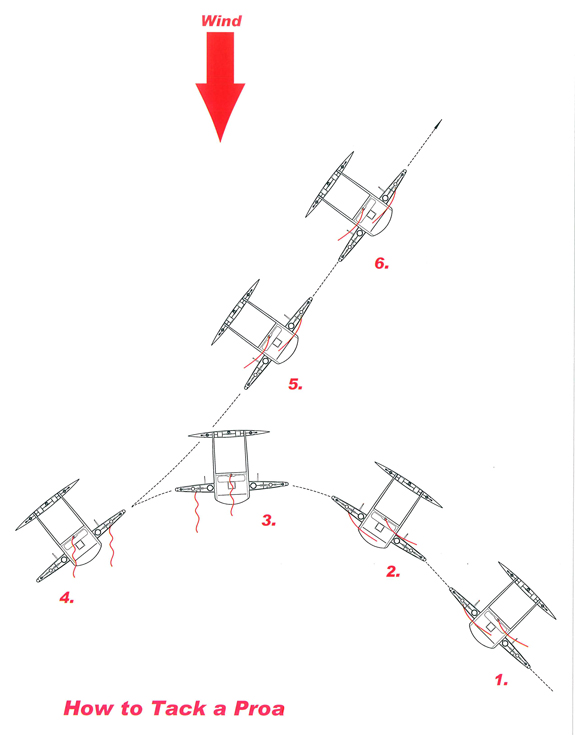

In the Western Hemisphere proas are still considered somewhat experimental, notwithstanding the pronounced success of “westernized” proas by Dick Newick and Russell Brown, which have accumulated tens of thousands of sea miles. As so few western sailors have experienced a Pacific proa (in which the outrigger is kept to windward), much is made of their tacking procedure: the boat is stopped, the boom swung around, and one bow is exchanged for another. On paper, this is a head-scratcher.

On the water, however, even a sailor with moderate experience “gets it” instantly, and falls under the spell of the proa’s peculiar handling advantages. Tacking a proa, a cause of confusion and concern among armchair sailors, is revealed on the water to be a casual exercise undertaken without the slightest drama, no matter the conditions. In a conventional western sloop of similar size and horsepower, tacking is a frantic exercise of flogging and fouling jibs, dangerous swinging booms, the risk of hanging up "in irons," and a delicate process of gathering way again on the new tack as quickly as possible. Jibes are worse.

In a proa, the boat is stopped in tacking and jibing, and is automatically hove-to with the mainsail feathered to leeward. It’s a good time to take a moment and grab a sandwhich or a jacket, something that would be unthinkable halfway through the tack aboard a conventional upwind boat. One jib is dropped and another hoisted on the new tack. When ready, you throttle-up with the mainsheet and presently you’re doing 15 knots on the new tack. The process isn’t ideal for short-tacking up narrow channels, of course, but I can't think of many 15-knot sailboats that are.

In a proa, the boat is stopped in tacking and jibing, and is automatically hove-to with the mainsail feathered to leeward. It’s a good time to take a moment and grab a sandwhich or a jacket, something that would be unthinkable halfway through the tack aboard a conventional upwind boat. One jib is dropped and another hoisted on the new tack. When ready, you throttle-up with the mainsheet and presently you’re doing 15 knots on the new tack. The process isn’t ideal for short-tacking up narrow channels, of course, but I can't think of many 15-knot sailboats that are.

Proas are the ONLY sailboats that can be reliably stopped, parked, and reversed on whim. In the headwind-in-a-narrow-channel scenario, you crank the outboard. (My 4hp two-stroke Yamaha yielded eight knots.) Otherwise, I have never been in any sailboat type that I’d rather maneuver into a crowded harbor under sail on a windy day.

Having gotten the handling idiosyncrasies out of the way, everything else about the proa configuration is absolutely compelling. No multihull can boast a lighter or easier-to-engineer structure. This pays off for the home-builder, who is spared the need for high-modulus crossbeams and attachments. There is simply less to build, and less complexity compared to a similar trimaran or a catamaran.

Proa sailors enjoy other handling advantages. Instantly noticeable under way is the comfortable motion in waves. The absence of the jerky, nervous pitching motion peculiar to cats and tris is easy on the crew and keeps airflow attached to the sails. The rig geometry of the Russell-Brown-style proa sloop opens a huge slot between jib and mainsail, making this kind of Pacific proa exceptionally close-winded.

Construction

Madness is built using techniques that are state-of-the-art for about 1975. (Not a typo.) 6mm okoume plywood panels are assembled very quickly using stitch-and-glue techniques, and sheathed on both sides with ordinary plain-woven e-glass. Nearly every component is pre-fabricated on flat workbenches. Building the prototype at Chesapeake Light Craft allowed us to dial in the fit of the CNC-cut parts, making it possible to offer kits for intermediate-skilled amateurs. Plans builders get full-sized patterns for most of the hull parts. (Thanks to the fore-and-aft symmetry of a proa, the longest pattern is just over 15 feet.)

Even without resorting to exotic materials, a very light hull is the result. Slung from my digital scale, the stripped main hull came in around 500 pounds. The outrigger, crossbeams, rig, and outboard account for another 500 pounds.

With sails, 4hp outboard, and basic cruising gear aboard, Madness weighs about 1400lbs, and compares directly with a Farrier F-24 in terms of SA/D—at a fraction of the cost and building complexity.

Accommodations

One trade-off compared to catamarans and trimaranas is that proas don’t have a lot of volume for their length. The payload is just under 1000lbs, sufficient to accommodate a singlehander for long coastal cruises, or two uninhibited adults for a week, or three to race the boat for a few days.

There are two berth flats fore and aft in the main hull, plus a wide, comfortable berth in the lee “pod.” On Hull #1, one of the berth flats has been converted to conceal a chemical head, and above it is mounted a lightweight galley that slides out of the way.

In good weather the crew might sometimes sleep on the trampoline.

The ama contains self-draining lockers for lines and fenders. I kept the outboard's fuel in the ama as well.

Handling

The skipper drives the boat from the motorcycle-sidecar-like cockpit adjacent to the cuddy. Draglinks are led from the tiller yokes to the cockpit. The crew occupies a comfortable “park bench” style seat on the trampoline to windward of the outboard sled.

The lee “pod” makes capsize very difficult. In four proas featuring a lee pod of similar proportions, Russell Brown has accumulated ocean crossings and 30 years of coastal sailing without managing anything more than a few knock-downs. Additionally, the outrigger is fitted to carry up to 700 pounds of water ballast. The ballast tank is filled using very simple and reliable plumbing: a bucket through a deck plate; it’s emptied with a bilge bump. However, in ten years of sailing Madness, neither I nor any of the other owner/builders has felt inclined to use the water ballast.

The mast is stepped on the windward edge of the cockpit, with all halyards right at hand. Winches and sheet cleats are located on the flange that stiffens the mast bulkhead. Because the mast is mounted 39” to windward of the main hull’s centerline, the mainsheets are led to struts protruding from the main hull.

The jibs are fitted with Code Zero-type furlers. In tacking, the current jib is rolled up, then doused completely to allow the boom to swing 180 degrees onto the new tack/ Then the “new” jib is hoisted and unfurled. The mast may be rotated through about 90 degrees for best performance.

Because of the mast location, there is no danger of losing the mast in an aback situation because it is supported by stays to the four corners of the boat. The very broad staying base allows a lighter mast, with spiraling improvements in decreased weight and construction simplicity.

Provision is made for an asymmetrical spinnaker.

Madness was fitted with the square-top rig shown in the drawings. A smaller “cruising rig” is meant to inspire builders to look for used masts and sails, which will cut the costs dramatically. (Madness’s carbon stick and Vectran sails cost more than the entire hull!)

An outboard of 2hp to 5hp is mounted on a retractable sled beneath the crossbeams, convenient to the skipper. Sea trials showed 5 or 6 knots with a 2hp in calm conditions, and up to 8 knots with a 4hp.

Transport

Madness is completely demountable for road transport. Six easily accessible bolts in the main hull and four bolts on the outrigger fasten the crossbeams. The trampoline is rigged with bungie cords for quick release, and two pins disconnect the outboard sled. A group of friends can lift the 500-pound main hull onto a trailer. The main hull measures 8’3” at the widest point, making trailering easy behind a relatively small vehicle. Total trailer weight is less than a Montgomery 17 pocket cruiser.