by John C. Harris

August 2015

This boat now has an official page, here.

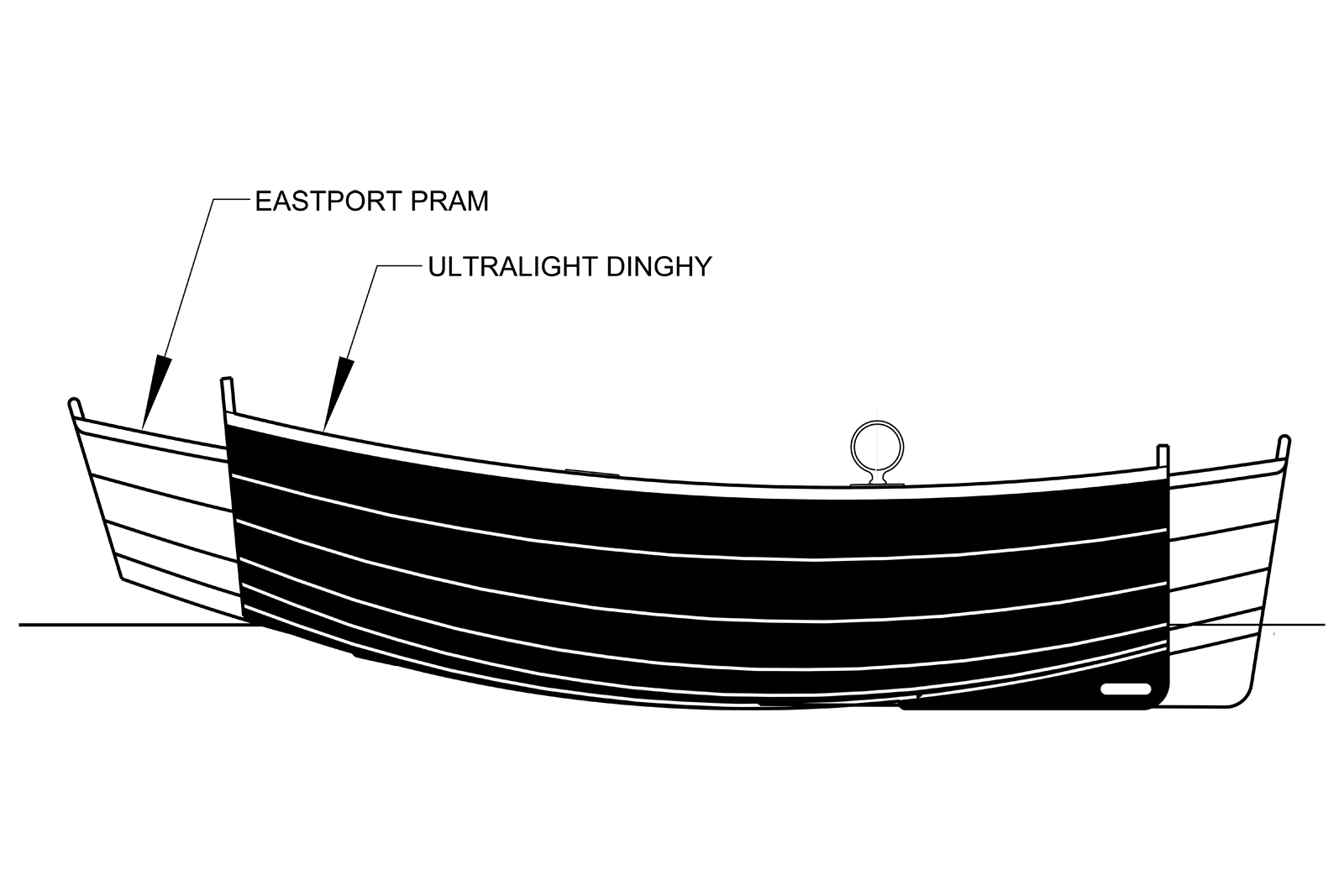

I have no delusions that any of my designs break new ground, a symptom of my neurotic personality. In the cold light of day, stitch-and-glue dinghies have been done before. Hundreds of designs. At most I could claim to have achieved incremental refinement of the type. Something like a thousand of my Eastport Prams have been built, and it's a very, very good dinghy. But I would hasten to observe that it's merely a collection of small improvements over lapstrake dinghies that were around a hundred years ago.

I have no delusions that any of my designs break new ground, a symptom of my neurotic personality. In the cold light of day, stitch-and-glue dinghies have been done before. Hundreds of designs. At most I could claim to have achieved incremental refinement of the type. Something like a thousand of my Eastport Prams have been built, and it's a very, very good dinghy. But I would hasten to observe that it's merely a collection of small improvements over lapstrake dinghies that were around a hundred years ago.

Build-it-yourself dinghies have gotten prettier, lighter, and easier to build, with the 7'9" Eastport Pram a paragon of the type. I have owned two myself, which served as tenders to a series of cruising sailboats. A carefully-built Eastport Pram weighs around 65 pounds, though 70 is not uncommon with a bit of extra epoxy and accessories aboard. This is very light for its capacity, but I have a new problem. And that problem is that I'm now middle-aged. When I designed the Eastport Pram I was in my late 20's. Hoisting the Eastport Pram over my head and onto car racks was easy, and routine. At age 43...something is wrong. That solo lift is now a struggle. It's certainly not something I want to do when I'm tired after a long day.

Thus I join an armada of yachties with the same problem: They need a tender for their big boat, and they need to be able to move it around easily. To and from the house on the car top, from the dinghy racks at the marina and over to the launch spot, onto the foredeck of the mother ship, and so on.

If, at this moment, you reflexively blurt out "Inflatable!", read no further. The redoubtable "deflatable" remains the default solution for most small yachts. They pack down small, they're as stable as a half-tide rock, and (sadly) no boatmanship is required to bring one alongside the mother ship.

Yet a percentage of us are snobs, and consider a fine lapstrake dinghy essential to the whole cruising aesthetic. And so it was that I resolved to build myself a wooden dink light enough that even my enfeebled carcass could hoist it onto the car or onto the storage rack without slipping a disc.

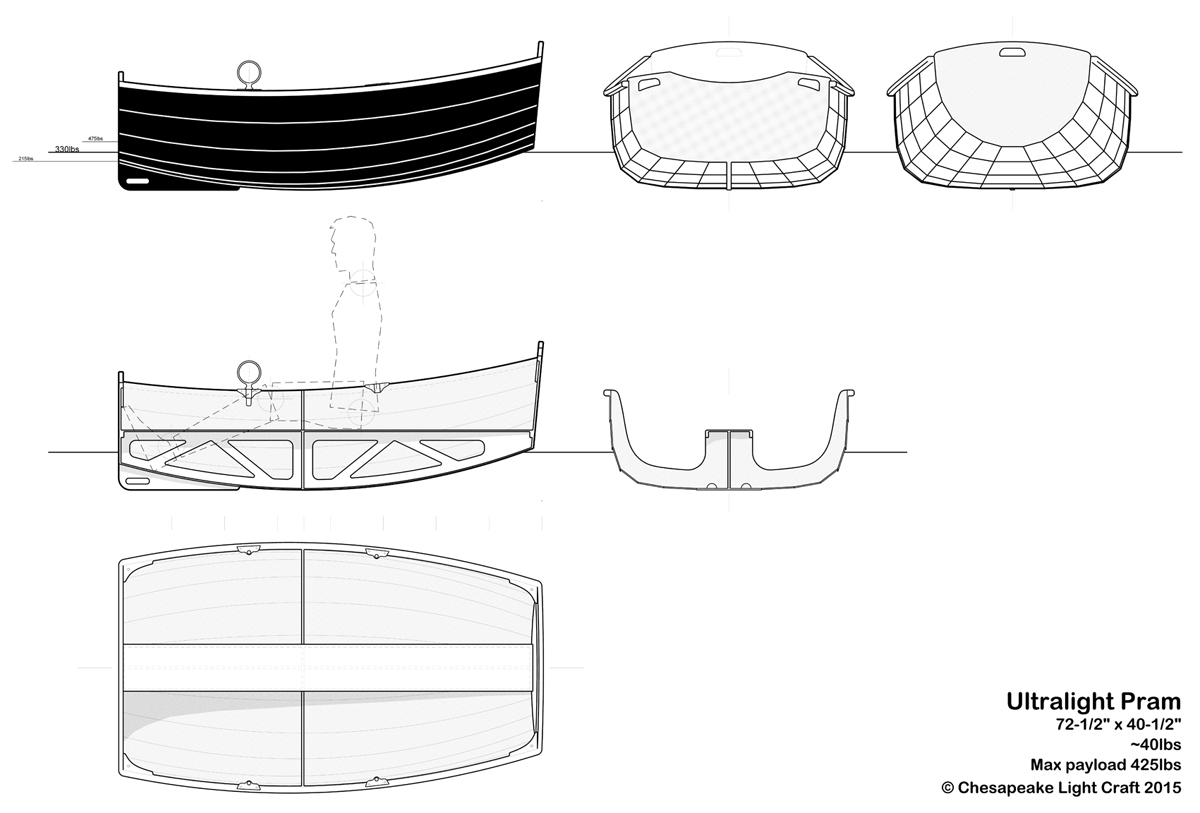

It would have to be very small, not only to keep the weight down, but so that it could be stored on the foredeck of a 27-foot sloop. Yet it would have to have payload and stability sufficient to carry myself, my wife, my daughter, and the groceries. I sketched and doodled, and at last settled on a 6-foot-long pram with a beam just over 40 inches.

A hull that's 55% as wide as it is long is comical in appearance. My first reaction was that I hadn't designed a small dinghy so much as I had designed a stitch-and-glue coracle. Coracles serve much the same function, of course: they're cheap, compact transport on calm waters. Obviously my tiny dinghy isn't going to row like a Whitehall, but in early trials I found that it could be rowed at three knots or more, which is faster than a brisk walk and a lot better than a coracle! Transporting a modest load across an anchorage at a fast walking pace is all we'll ask of this little boat, and it has achieved that goal.

A hull that's 55% as wide as it is long is comical in appearance. My first reaction was that I hadn't designed a small dinghy so much as I had designed a stitch-and-glue coracle. Coracles serve much the same function, of course: they're cheap, compact transport on calm waters. Obviously my tiny dinghy isn't going to row like a Whitehall, but in early trials I found that it could be rowed at three knots or more, which is faster than a brisk walk and a lot better than a coracle! Transporting a modest load across an anchorage at a fast walking pace is all we'll ask of this little boat, and it has achieved that goal.

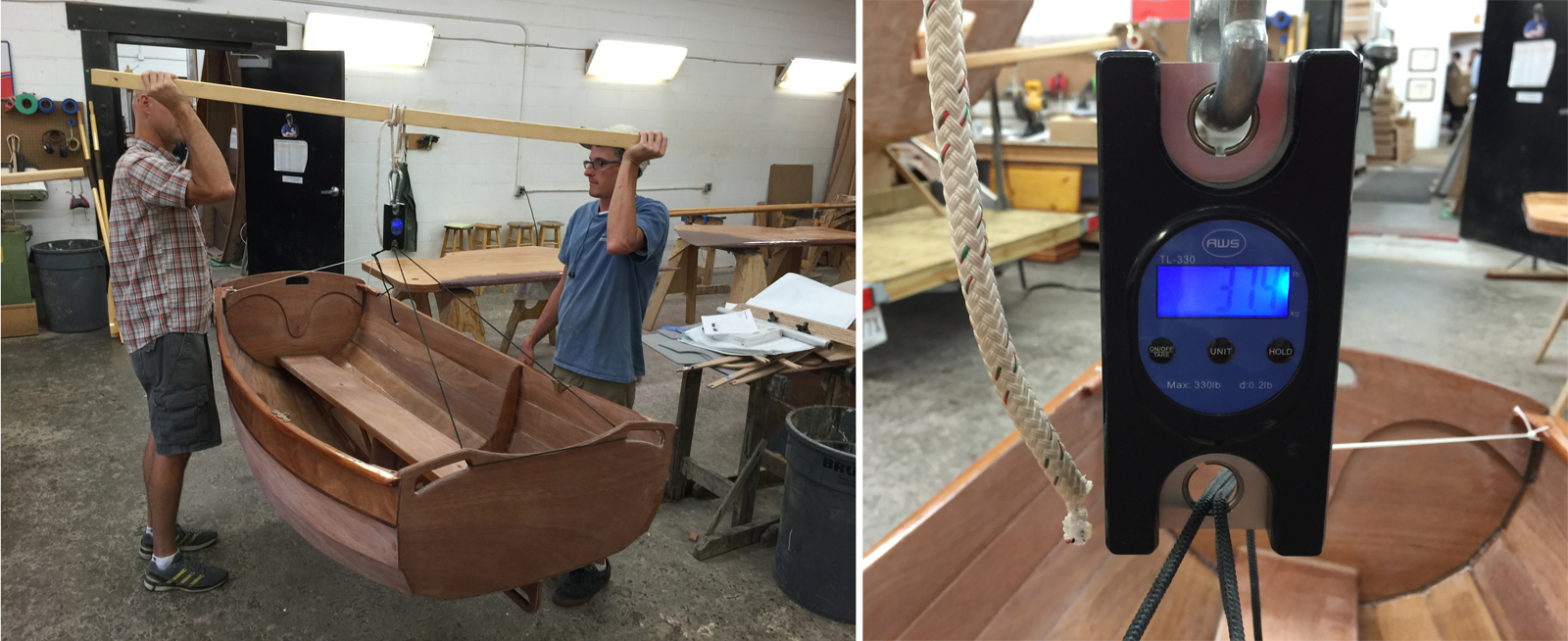

Our digital scale reports 37.4 pounds. Call it 40 by the time I add paint and varnish, a second pair of oarlock sockets, and gunnel guard. I can lift 40 pounds over my head even on a bad day, and I was able to carry it a quarter-mile to its first launch at the WoodenBoat School last week.

The centerline rowing bench is in the perfect spot to function as a carrying handle, with the rail hooked on your shoulder.

So far the heaviest load I've had aboard was 380 pounds, and this didn't seem to slow the boat down any. It can take more. The freeboard is high, actually an inch or two higher than the Eastport Pram's, to make it harder for spray to get aboard and allow for a lot of reserve buoyancy. With six-foot oars you have so much power compared to the boat's weight and wetted surface that it seems unconcerned with windage. It tows light and dry when empty, with the bow transom well clear of the water.

We built the prototype in the booth at the WoodenBoat Show in Mystic. Three days of sporadic work were sufficient for assembly, fillets, and interior fiberglass. I suppose it's a 50-hour project if you finish her out nicely. As of this writing I've yet to get paint and varnish applied, so the photos here just show the boat with sanded epoxy over everything.

The Ultralight Dinghy has been everything I'd hoped for. An easy lift, capacious, rows well, and it's about as dry as you could hope for.

Now for the downsides.

First, there's no escaping the physics of a boat this small and light. Stepping aboard will not be like stepping into a Boston Whaler, or even a small inflatable. You need to be able to shift your weight in one smooth motion from dock or mothership to a seated position in the dinghy. Hesitate during the transfer of weight and the boat will slip out from under you like a banana peel. You'll use the same caution in embarking as you would in a canoe or a beamy kayak that weighs 40 pounds. It's entirely manageable if you're used to getting into boats with so little inertia, but someone going from a 140-pound inflatable to this dinghy might be startled and wet, in that order.

There's plenty of stability once you're aboard, and especially once you're seated.

Second, please don't write in asking me what size outboard you can mount. The answer is: None. The boat is just too small. If you're so feeble that you can't row this boat a couple of miles, you're probably not nimble enough to get in and out of it anyway.

Third, ditto on the sailing rig. There isn't one, and there never will be. Bring a golf umbrella along as a downwind sail. Build an Eastport Pram if you must sail; it's incredibly good at that.

Fourth, beware of an important trade-off in keeping the weight down: there's no built-in flotation. The boat is wood so it's not going to sink if swamped, but you couldn't self-rescue. Since I was designing for myself I can rely on being a smart and careful boatman to avoid mishaps, and I always wear a life-jacket. It would be possible to fit enough foam under the centerline bench to allow a wet rescue, and it wouldn't add much weight, but the foam could make it more difficult to carry the boat on shore (you lose that vital hand-hold), and harder to place your feet near the centerline as you step aboard.

And finally, another compromise in creating an ultralight dinghy is that the thing is built with a thin hull shell. It's all 4mm plywood. The lower half of the hull is fiberglassed inside and out, while CLC's LapStitch™ joints provide stiffness to the topsides. It's rugged enough for casual usage, but some bad luck with a nasty bolt sticking out of a piling or a bad drop in the parking lot could cause damage. You'll have to exercise more caution in the dinghy park than you would with a bigger, heavier dinghy.

I'll be curious to see the reaction to this highly functional little dinghy.

This boat now has an official page, here.

A complete kit, including all of the CNC-cut and -drilled okoume plywood parts, mahogany rails, seat components, epoxy, fiberglass, copper wire, syringes for tack-welding, and a set of oarlocks and sockets comes to $829.

If you want just the wood parts only, the CNC-cut and -drilled components, rails, and seat, that would be $499.

You can read basic instructions (intended for someone with some knowledge of epoxy and fiberglass) in wiki form here.

return to section:

return to section: