The Most Peculiar Client

The Most Peculiar Client

December 2018

After almost 25 years of being paid to design small boats, I thought I'd seen it all, but this design inquiry came out of left field. While most people are looking for simple and cheap, this individual was not. While most desire shoal draft and ease of trailering, that was not a major consideration. And while nearly every sailor with whom I correspond is fixated on the engine arrangement---not the sailing rig---this client clung stubbornly to the notion of sailing engineless.

My client is a lifelong sailor who's owned just about every sort of boat. He---and alas, they almost always seem to be a "he" in this line of work---has very strong ideas about what he wants. And some of his ideas were very old-fashioned, indeed. Pushing well into middle age, he was starting to think about the "boat for the rest of his life." After owning big, heavy cruisers, racing dinghies, fast multihulls, and everything in between, he wanted a trim little pocket cruiser that would see him comfortably into his twilight years. He knew that what he had in mind would be expensive (an awareness that is ALWAYS appreciated at this stage by the designer), but planned to keep the boat for long enough that he would get his money's worth. It would be an unusual boat, and thus hard to sell, but that would be his heirs' problem, not his.

The client had owned a heavy 26-foot sailboat with a full keel and no engine. Reflecting on every boat with cruising accommodations he'd ever owned, he was convinced that the engineless 26-footer had been the best all-around sailboat of them all. From a life of sailing experience his best memories were of wafting up to a mooring on the last of the evening breeze, of slicing to windward in heavy air while the boat steered itself, and of occasionally startling larger, sleeker boats with the speed he could coax from the clean-lined 1940's design.

Unlike the 26-footer, however, he would build this one himself. He'd built many boats and was unconcerned about complexity, within reason. This was another relief to the designer. As for size, he set a peculiar filter: it was to be the smallest possible boat that could fit a wood-burning marine stove in the cabin. Not just in terms of physical space, but functionally as well. You need a certain tonnage so that while at anchor the wake from a passing motorboat won't knock the tea kettle off the stove, or shake the coals out onto the cabin sole.

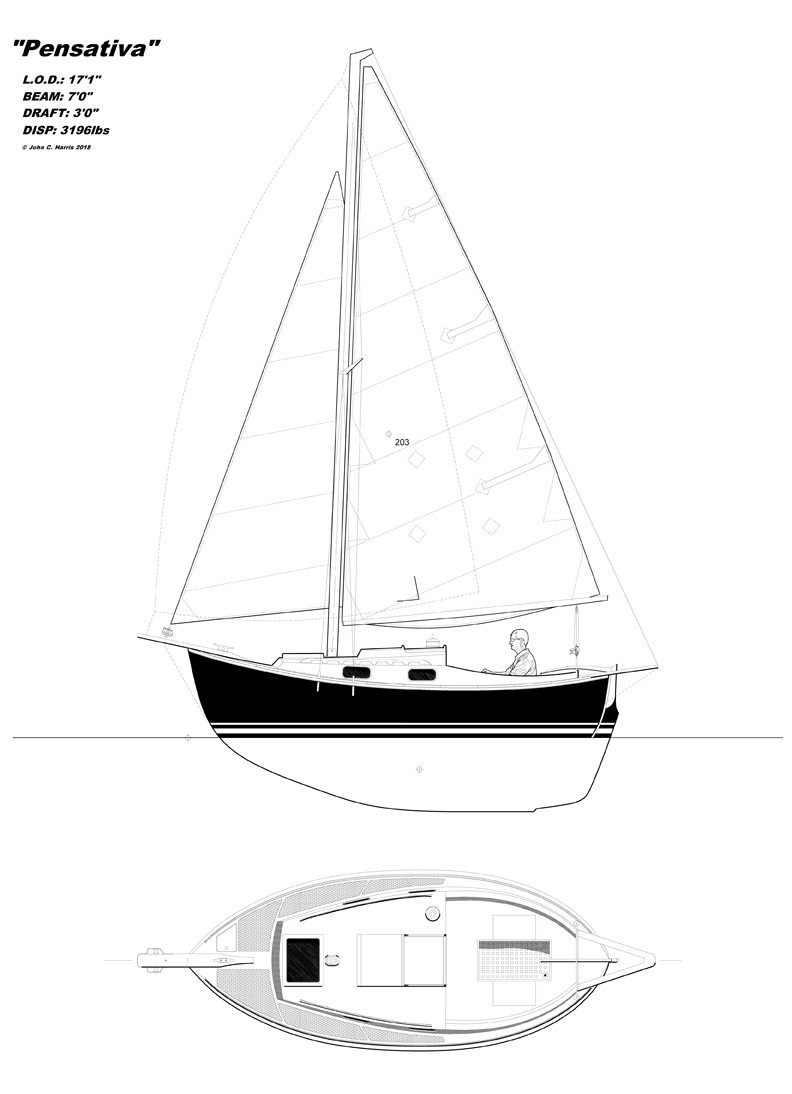

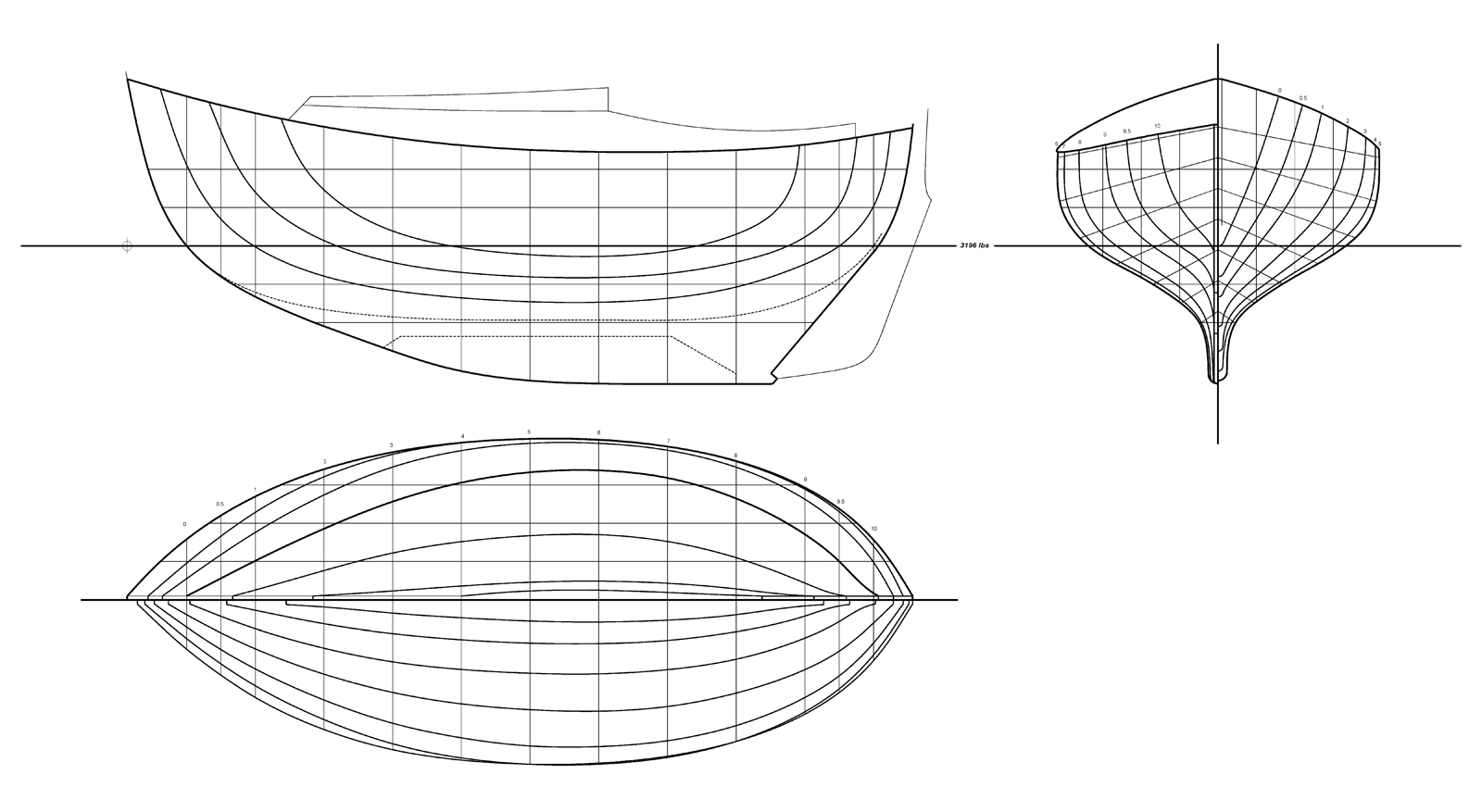

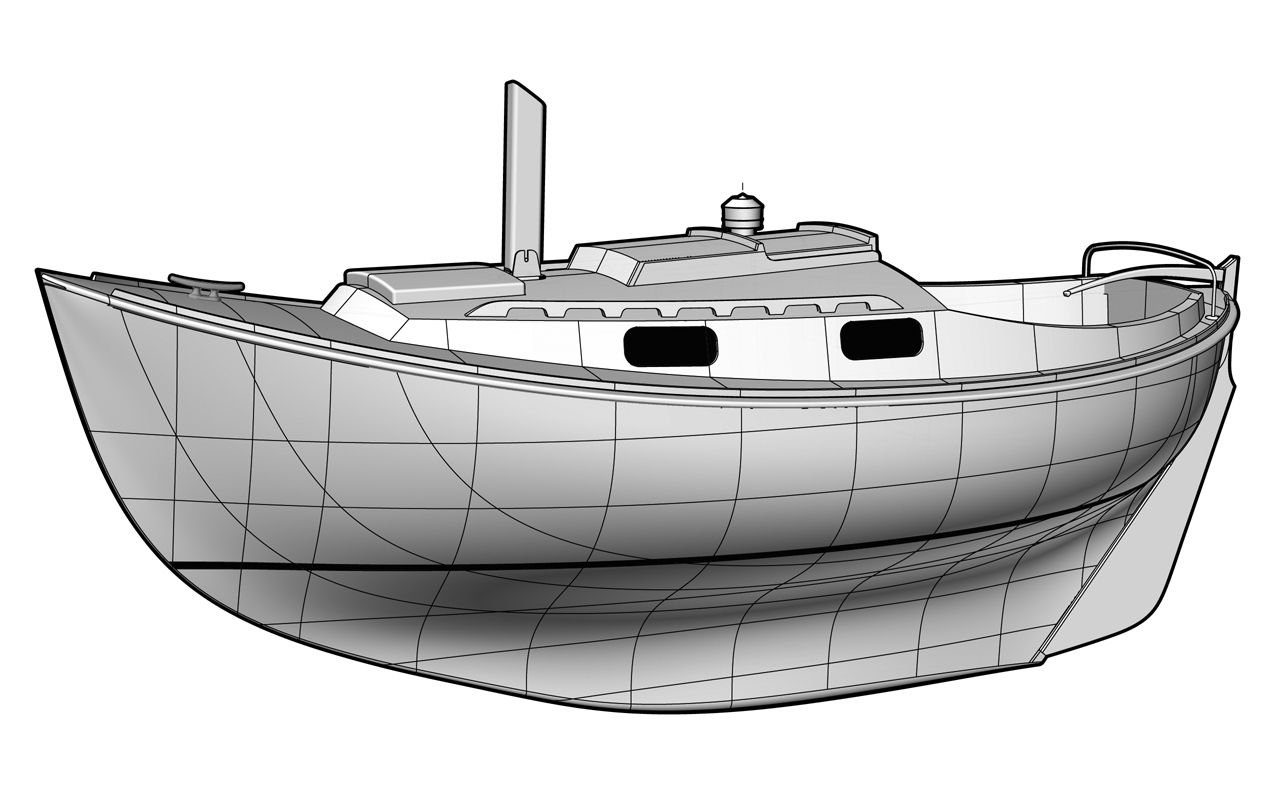

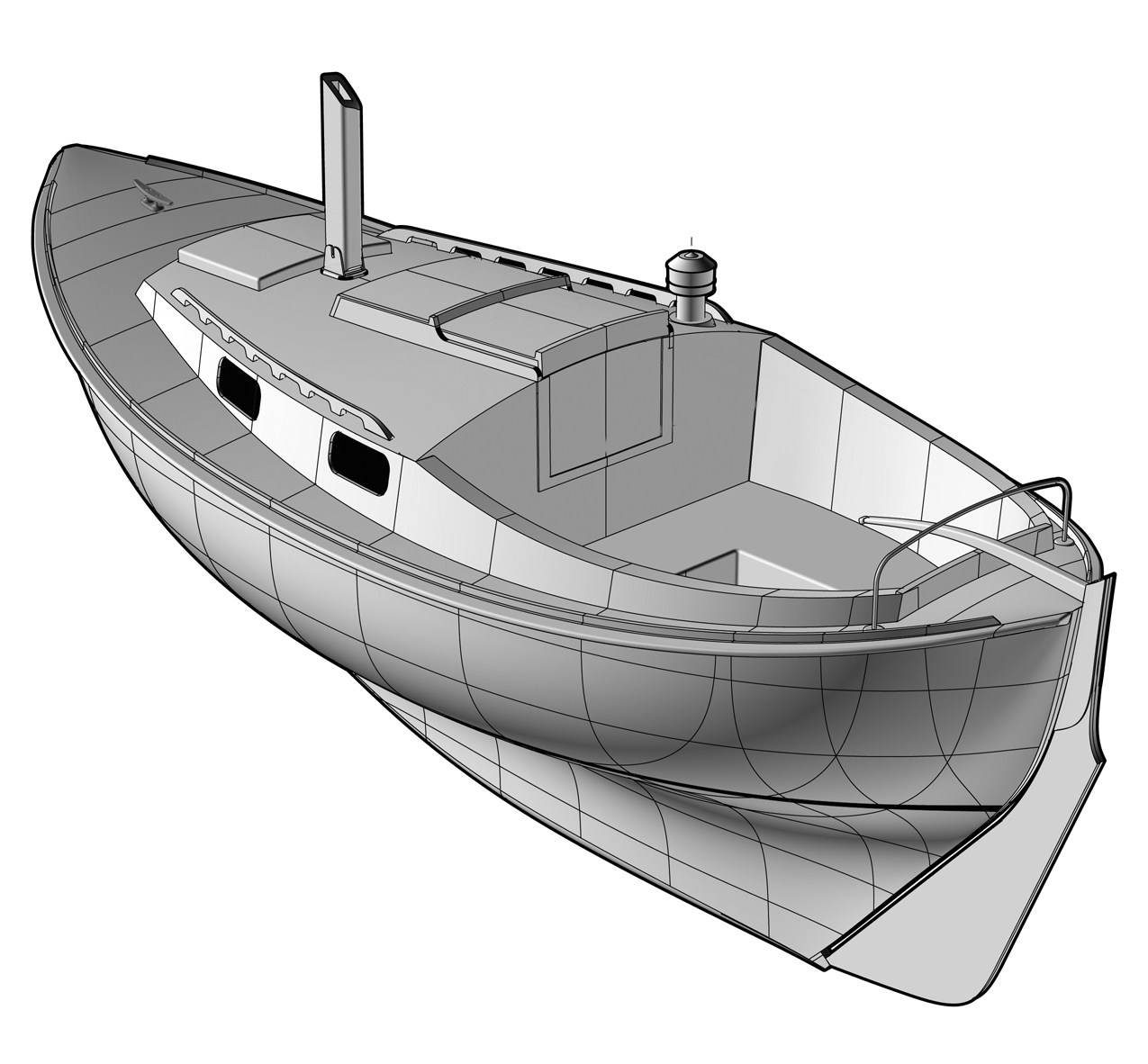

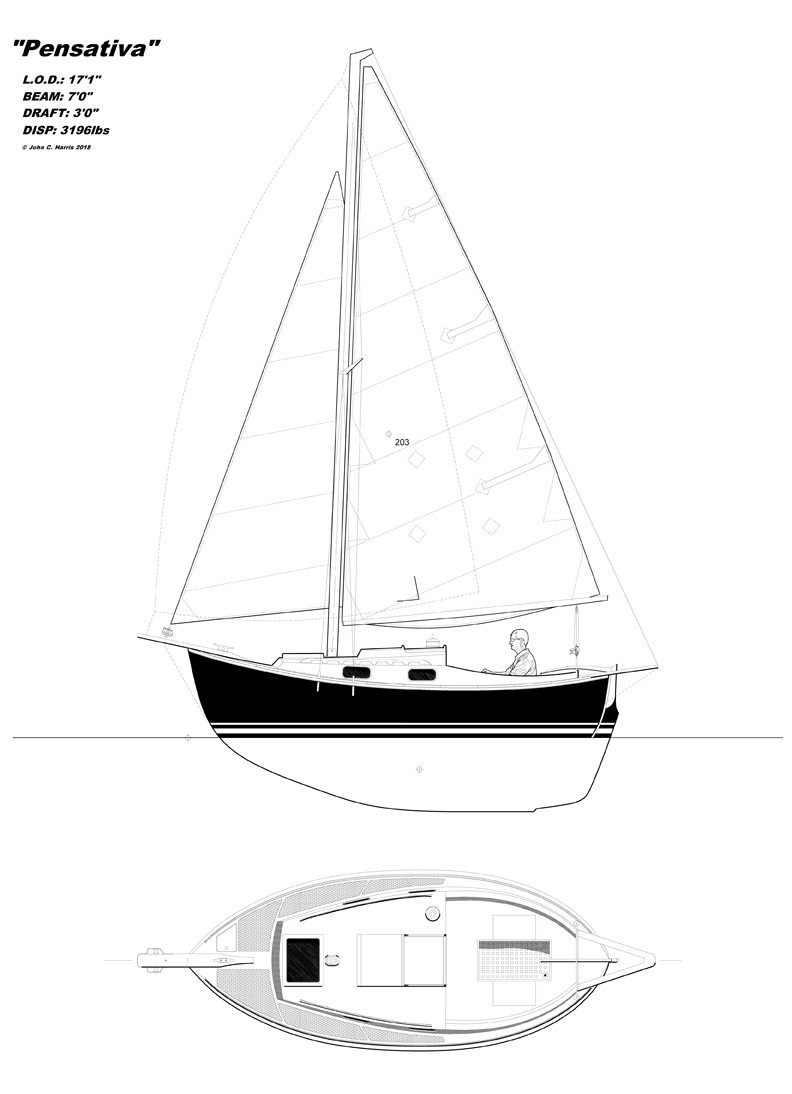

This single feature established many of the parameters. It would be a heavy, full-keeled sailboat with a high polar moment of inertia. I thought that 17 feet was the smallest length-on-deck that combined a comfortable cabin with reasonable performance.

And performance is a BIG deal to this client. He'd been on enough heavy boats to understand that heavy doesn't have to mean "slow." Given nice lines, a clean bottom, and a powerful rig, heavy-displacement boats can be slippery and even fast in light-to-moderate air. (Cruising boats with shallower hulls and fin keels will be faster in heavy air, but only if they have the stability to stand up to their sail.)

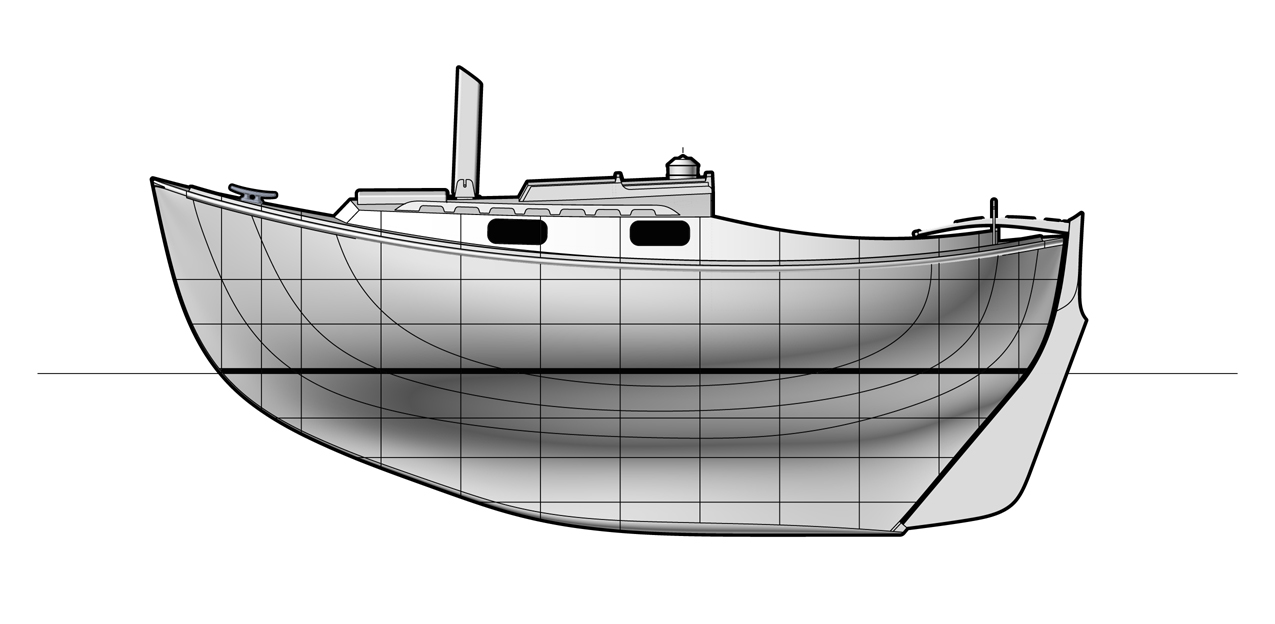

I was confident I could wrap a set of hull lines around a ton-and-a-half of displacement and still have a boat that would be fun to sail. There's a persistent misconception that deep-bodied boats like this are innately slow. Most people have only experienced tired old versions of this hull shape. Such boats invariably have incredibly rough finishes below the waterline: planking like the side of a barn, roughly caulked seams, a huge propeller dragging like a bucket, a dozen through-hulls. Imagine the underbody of this boat perfectly smooth and fair, and kept that way with frequent hauling and a hard-finish antifouling paint.

The canoe stern wasn't a given but we both liked the looks. Without the need to hang an outboard engine on the stern, we were free to have fun with the sculptural details. A transom, even a small one, would flatten the buttock lines aft and offer more top-end speed as well as additional hull volume for the cockpit and lazarette. I can't think of any real advantage of the pointed stern, either in terms of performance or ease of construction. Such a stern is certainly not "more seaworthy," a trope that's been repeated in boat design circles for a hundred years or more. Mostly it just looks nice.

The client didn't blink an eye at the 36-inch draft. His beloved 26-footer draws four feet, and he claimed that this had never kept him out of an interesting harbor on the Chesapeake. Three feet is only five inches deeper than the much-loved Cape Dory Typhoon, and still shallow enough to allow trailering given a deep ramp and a high tide.

The client had Very Strong Opinions about the rig. He wanted a tall, modern sloop with a roller-furling jib. He was not interested in affectation of any kind. There would be no deadeyes, no polished bronze, no baggywrinkle, no cute little jib staysail. His rig would be aerodynamically clean, using the latest upscale go-fast hardware. This was all in service of his preference for engineless cruising. No other rig, he asserted, was as good at pinching and short-tacking up a narrow channel in marginal conditions. Phil Bolger once remarked sardonically that he never had any trouble making a boat sail downwind, a jibe at the people who dismiss the importance of upwind sailing efficiency. I love my little gaffers and cat yawls, but sometimes the difference between making an anchorage by nightfall or before a squall hits comes down to your upwind VMG. His 26-footer had an uprated, modern fractional sloop rig and he recounted feats of navigation he swore weren't possible with any other rig.

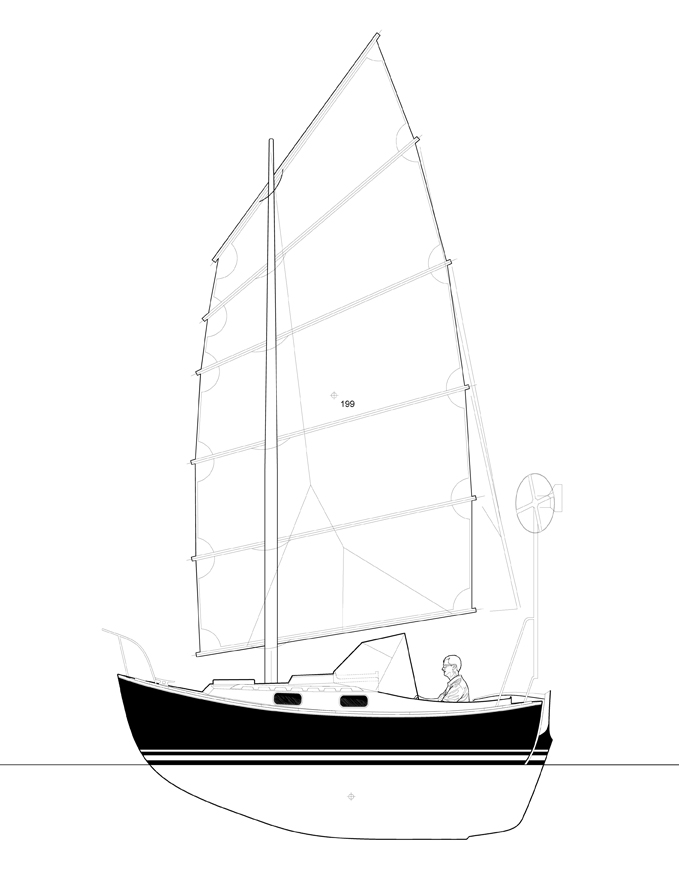

We parted ways on the bowsprit. He wanted the rig entirely inboard, with no backstay. This was awkward to arrange and still supply something like the SA/D numbers needed. We ended up with a very tall mast and a skinny mainsail, supported (precariously) by side shrouds raked aft, as in racing dinghies. He was happy with this, but several people who looked at the drawing commented that the all-inboard rig wasn't a great compliment to the nice lines of the hull. I agreed and drew a version with a bowsprit. By spreading out the sailplan a little I was able to knock two feet off the mast height without losing any area, and the balance compared to the CLR was much improved. I added a boomkin and a fixed backstay, arguing that if he needed to make safe harbor in an autumn gale, a backstay was a wise addition.

The bowsprit and boomkin add four feet to the boat's length overall, which made the client very cross. He also despised the additional time required to construct, outfit, and install those components. I countered that he now had a nice place to stow his anchor, a point he conceded grudgingly. It doesn't seem unreasonable to me to spread out the sailplan a bit on a sailboat that's carrying 3200lbs of displacement on a 14'9" waterline!

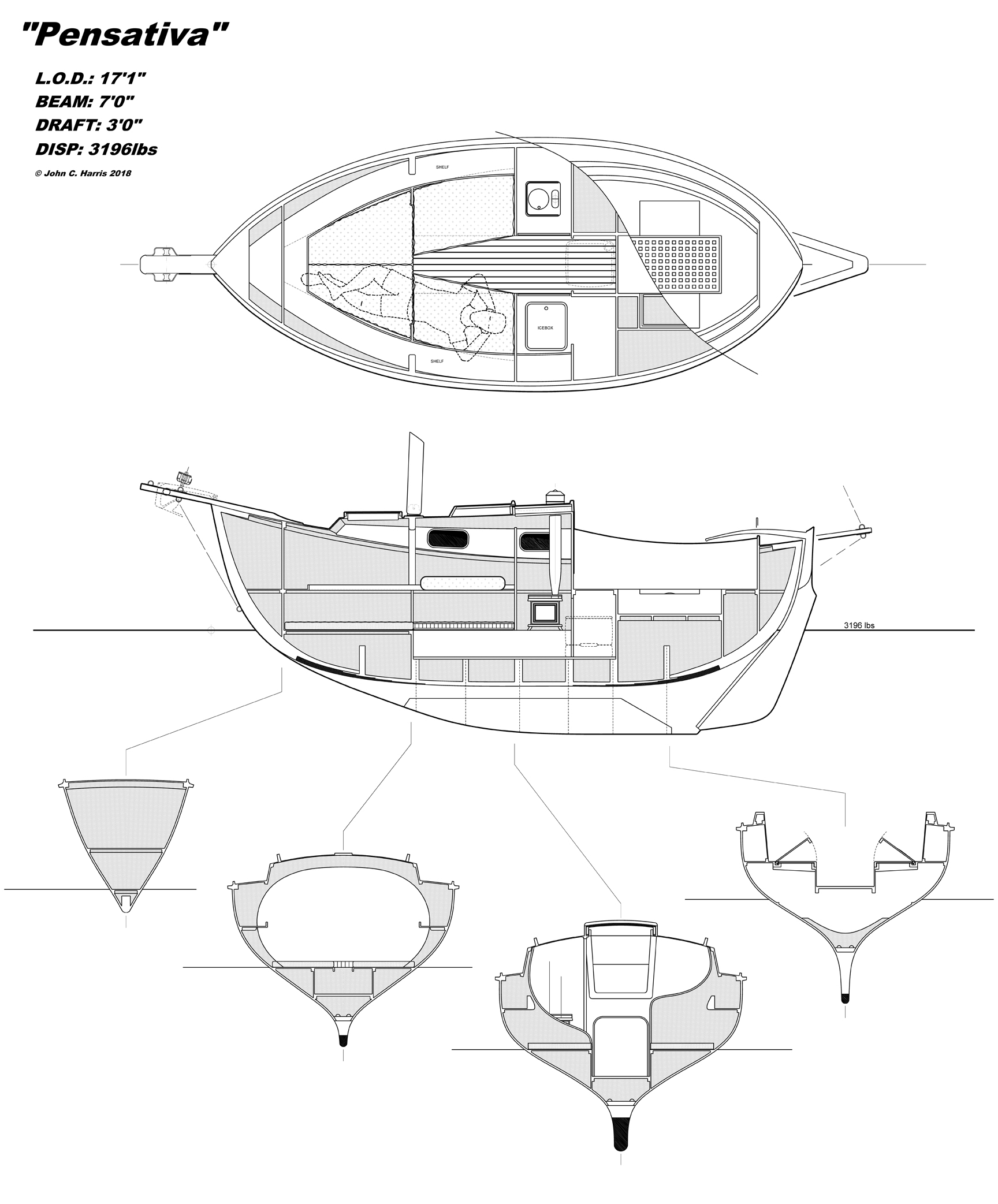

One of the upsides of being such a "big" little boat is that the cabin is commodious, at least in comparison to the usual sitting-headroom trailer-sailer. We're pondering three or four different interior layouts. The first and most "normal" is the one shown above: an ordinary V-berth for two adults, with a galley and stove aft. The chemical head hides under the bridge deck and is pulled out for use. One person could cruise coast-wise for weeks in such a cabin, dry and well-fed.

For two people, this is a weekender proposition unless the couple packs very light. While a singlehander by temperament, he thought his young daughter might join him for occasional short cruises, so this layout remains in the running.

Another option has two quarter berths aft, a small galley amidships port and starboard, and a head and lots of storage forward. This would be the preferred arrangement for the dreamers who would consider cruising off-soundings in a boat like this. (For the amusement of such self-punishing types, I've shown a junk-rig option.)

A third option is an open, "romper room" interior, used with such success in PocketShip. In this case we'd just have a broad spread of nicely-oiled floorboards, and not much else. The stove could still be there, and the head in its cubby-hole under the bridge deck, but mostly it'd just be open space. You'd sit on outdoor-grade beanbags, and roll out camping cushions to sleep, sparing you thousands of dollars in custom upholstery. There'd be more head- and legroom without all of the dollhouse-scale built-in furniture. Gear would be stored in zippered bags running down either side of the cabin beneath the side decks. (I've used bicycle saddle bags for this in similar boats.)

The "romper room" option would also save a hundred hours or more in construction, a point that has made my client at least willing to give that layout some thought.

The construction of a boat like this is the agitated elephant in the room. 2000 hours in skilled hands is my educated guess for a yacht finish. At the client's behest, the boat is of strip-planked softwood with a heavy sheathing of fiberglass inside and out. This wood-epoxy composite "sandwich" approach is a long slog to build and expensive in materials but would guarantee a very strong and nearly maintenance-free boat. At a glance I think the hull could be built in glued plywood lapstrake, an approach that's much quicker and cheaper given professional skills. The client vetoed this option because he dislikes the parasitic drag of the lapped planks below the waterline. Once a racer, always a racer, I guess.

2000 hours of construction escalates this undertaking from a fun lark in the garage to a consuming, life-altering commitment. Someone like me who's still working for a living and has family obligations couldn't do it in less than two or three years. Given 21st-century distractions, a five-year build time would be normal.

Put in 40 disciplined hours a week and you could finish the boat in a year, give or take. Turn the project over to a professional boatbuilder and you're looking at $100,000 for the labor alone, plus materials. Call it $125,000 on a trailer, ready to sail. If that sounds outrageous, you can understand why boats shaped like this are no longer manufactured. (I dare you to commission a brand-new Pacific Seacraft "Flicka." Or even something the size and shape of a Cape Dory Typhoon.) I'm using $50/hour for labor, the lowest rate you're going to pay in the United States for a professional with the requisite skills, shop space, and liability insurance. And if you still think that's outrageous, the guy who works on my Volkswagen charges $75/hour, as does the guy who spreads mulch in my yard.

The question of how much you should pay someone to build a boat like this is fodder for another post sometime...

In the event, the client means to build the boat himself, and from long experience has the requisite skill to set up a mold, whittle all of that deadwood, cast a heavy lead ballast keel, and in general bring up a professional finish.

* * * * * * * * *

If you've read this far, you have either deduced the identity of the mysterious client, or you deserve to know. The client, of course, is me. The fictional give-and-take between client and designer outlined above was, in fact, far more fractious and unruly than indicated. "You are certifiable," I told myself while sketching out the design in evenings and weekends. "It took you three years just to finish a 10-foot dinghy in your spare time." (The 26-footer is my Tord Sunden-designed Marieholm International Folkboat.)

The fun ideas are always the crazy ones, and this sort of daydreaming is how I've kept a fingernail-grip on sanity since I was in grade school. It's not impossible I make the time (or find the money) to see it through one day.

I've met many people over the years who appreciate boats like this. Even a few who have built boats of this tonnage and complexity. But honestly I don't know a soul who would take up the challenge. If it helps push you over the edge, note how much empty space I've left under the cockpit and bridge deck to fit that god-damned engine you can't live without.

return to section:

return to section: