Ollie: Yet Another Canoe Yawl

By John C. Harris

February 2022

|

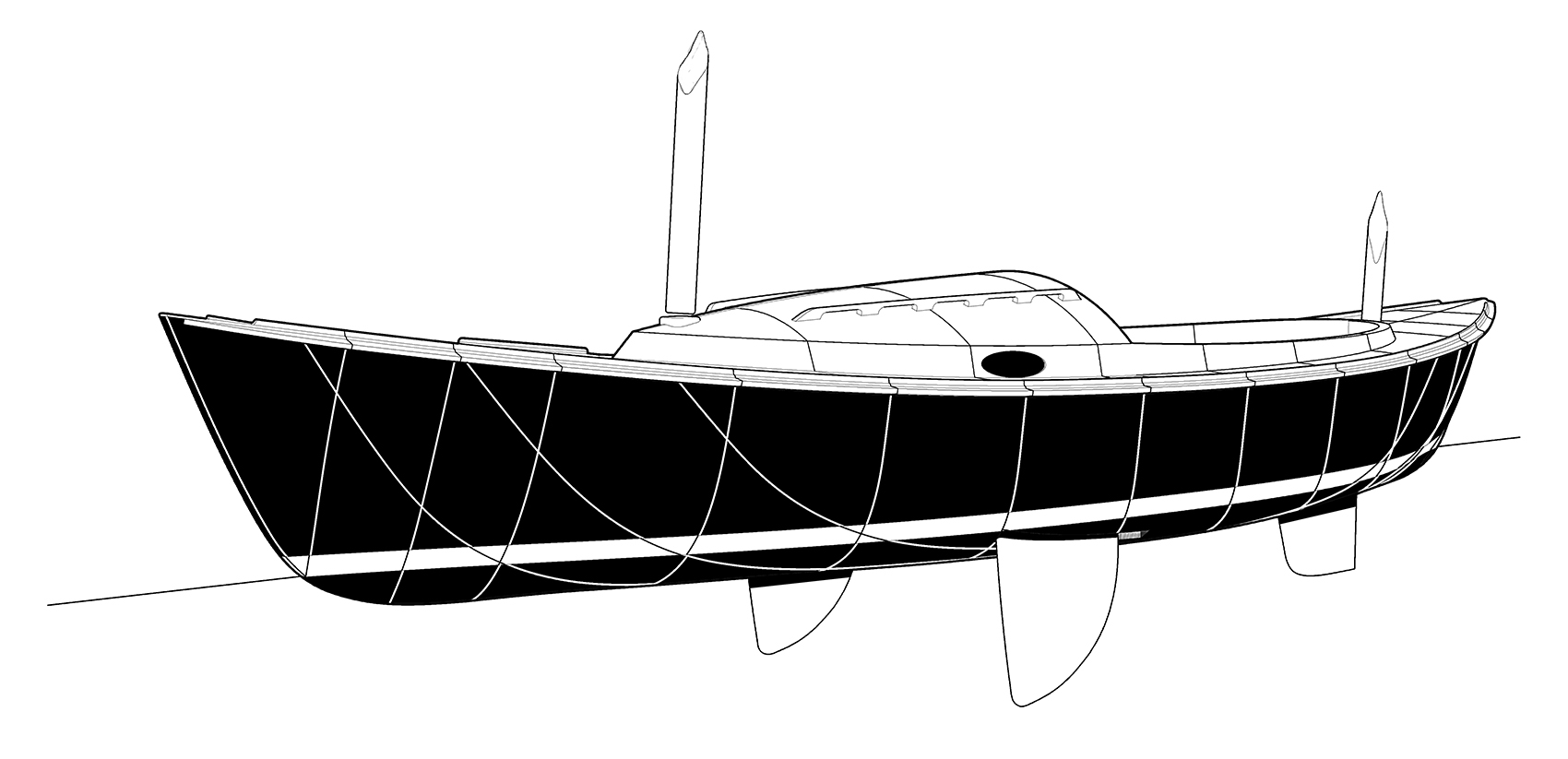

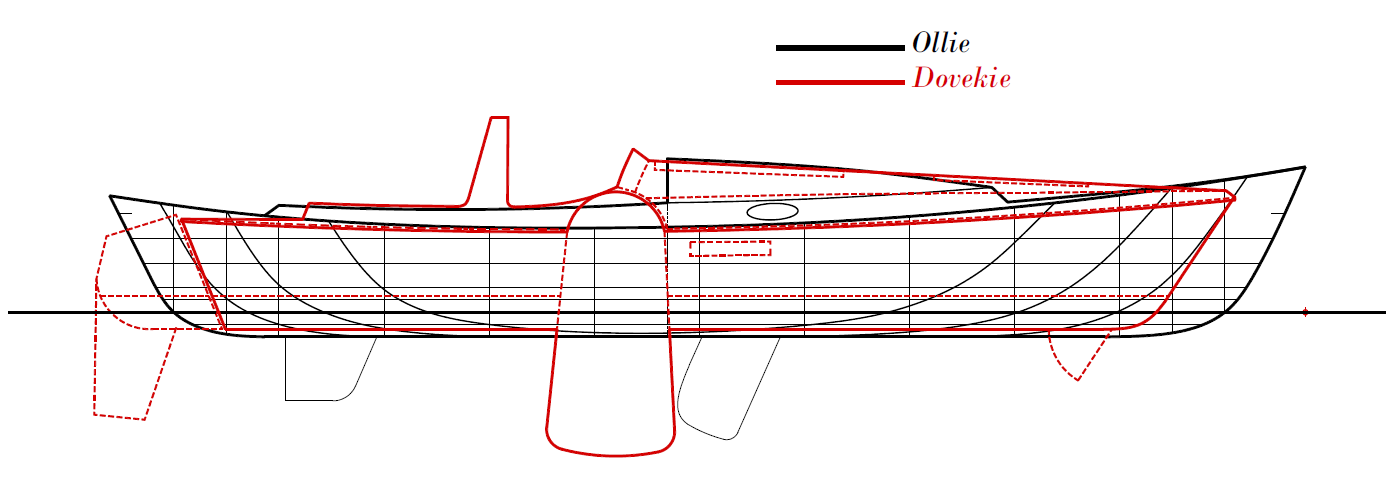

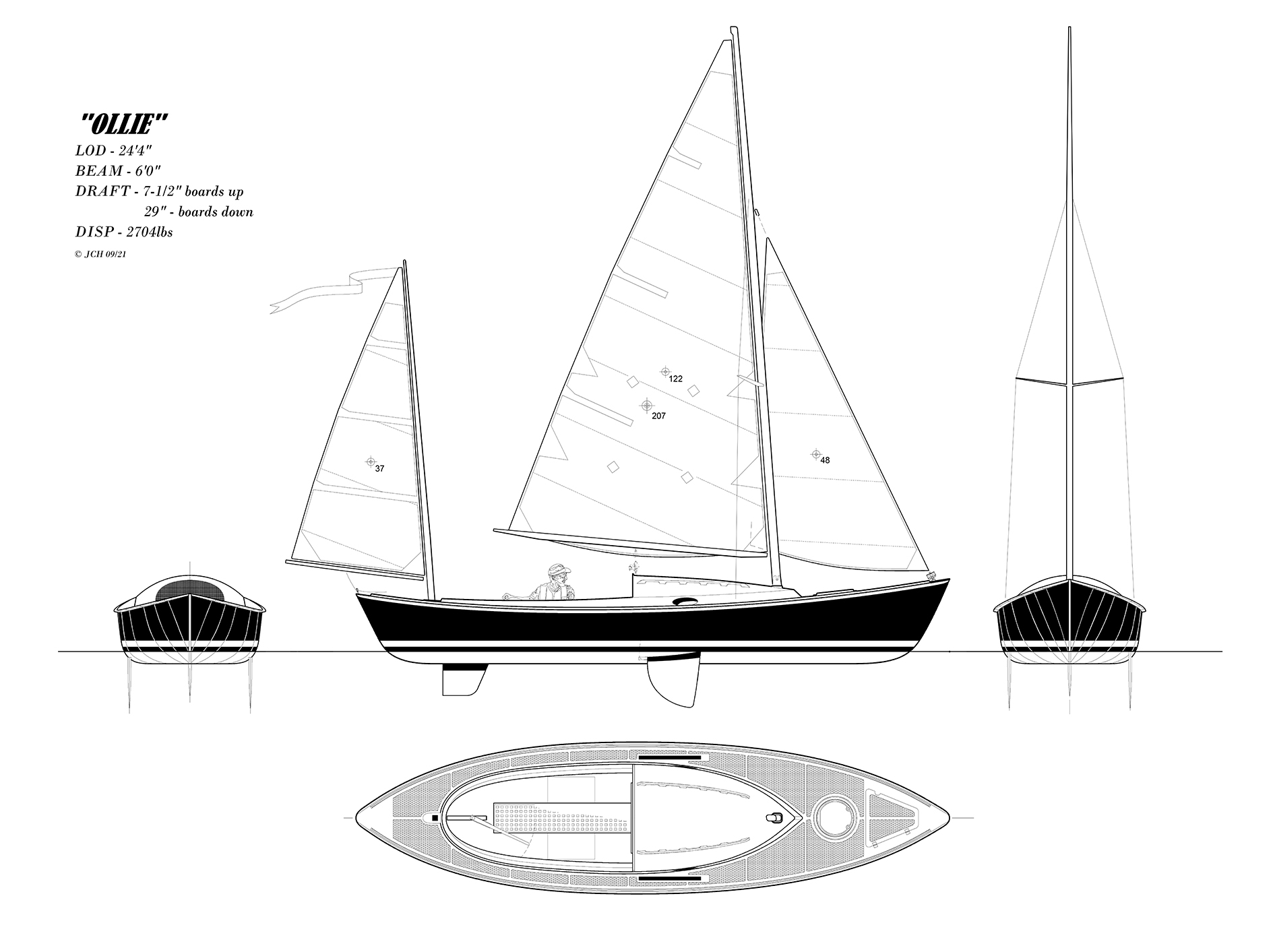

| "Ollie," a neo-classical canoe yawl 24'4" x 6'0" 7.42m x 1.83m Draft 7-1/2" boards up, 29" boards down Displacement 2704lbs (1227kg) |

I've written often of my lifelong vice of daydreaming, to the detriment of school grades, deadlines, paying work, and in general being present in the world. My 6th-grade math teacher in my home town of Aiken, South Carolina would catch me drifting away. In a slow southern twang as thick as peach marmalade and loud enough to be heard across the hall, she'd ask: "You pickin' daisies again, Jaaawwwnn?"

Here's another daisy, Mrs. Winn.

Besides the time consumed by drawing boats that no one asked for, much less hired me for, this sort of distraction gets me in trouble in other ways. If I'm sufficiently tickled I might circulate sketches on social media, purely for entertainment. "Ollie" got the attention of Mike O'Brien, design editor at WoodenBoat, and Bob Perry, who holds the same chair at Sailing magazine. As luck and the editorial calendar would have it, Ollie would slot in nicely for both of them. I finished the weight studies and construction details, and just like that Ollie was in print...before I had a chance to post anything on CLCBoats.com about the boat, or to complete drawings suitable to sell to prospective builders. Not for the first time...

Ollie is inspired by the Phil Bolger/Edey & Duff rowing-sailing design Dovekie, a boat I've loved since I first saw ads for it in my early teens, and about which I've written often. Two decades later I owned a Dovekie at last. And to my surprise, I was never happy with having to crawl on hands and knees under the deck, as the designer intended, to douse the sail or deploy the anchor. A beautiful, original design, but I never learned to live with her quirks the way some Dovekie owners did.

Ollie uses Dovekie's unusual hull shape as a departure point, but has a conventional deck layout. She's also three times heavier and carries inside ballast.

For the internet blathering class who find all this tl:dr, I'll put this in bold italics: I do not represent Ollie as an attempt to "improve" Bolger's Dovekie design. If you're looking for Dovekie's singular features but, like me, can't quite make peace with her ergonomics, the natural progression is to Bolger's brilliant but underappreciated Birdwatcher design. Birdwatcher checks all of Dovekie's boxes and a bunch more besides, including the ability to build her quickly at home.

The sea bird known as a Dovekie is genus Alle, species alle, pronounced "Ollie."

|

|

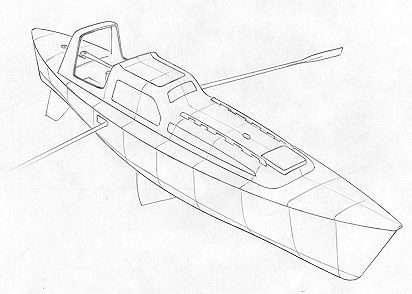

A freehand sketch in one of my old notebooks, dated 1997. Clearly a meditation on Bolger's Dovekie design, with a revised deck layout. |

|

|

A sketch of Dovekie #135, which I owned for a few years, from |

|

|

Ollie in black, Dovekie in red. This early drawing shows slightly |

Both Ollie and Dovekie are descendants of the classical canoe yawls: slender, easily-driven, capable boats, with minimalist accommodations and the pretense that they can be enjoyed without resorting to auxiliary engines. A century later, people still admire the canoe yawl ethos, as evangelized by George Holmes, Albert Strange, and their acolytes, but there are few practitioners. The earth spins too fast these days to synchronize your cruising to the wind and tide.

After many false starts I got a thoroughly modern canoe yawl design to work: Autumn Leaves, a fine sailing machine with sitting headroom and simple carpentry for the home builder. But the plywood Autumn Leaves lacks the immortal grace of Strange's Sheila II or LFH's Rozinante. What I wanted to do was to capture the vibrance of those revered designs, but spare builders the harrowing complexity of their construction.

I'd pondered vandalizing an old Dovekie by adding a nicely proportioned deck house, ballast, and a more sophisticated upwind rig. Ultimately this was a heresy I couldn't abide, and that's how I found my way to the heavier, more shapely Ollie. The ballasted Ollie can be driven harder under sail, and benefits from a less idiosyncratic cockpit and deck layout compared to Dovekie.

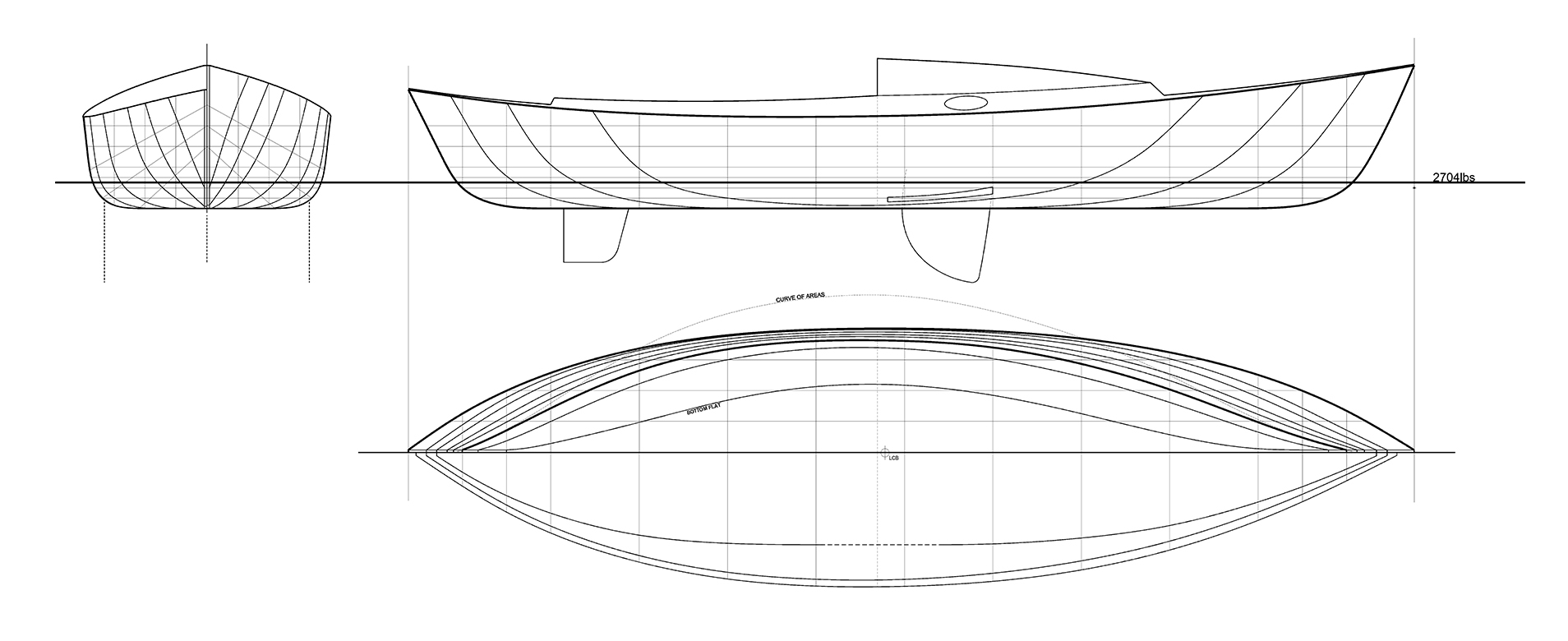

Ollie has a swoopy sheerline and elegant concavity in the lines at the bow and stern. But the hull fairs into a dead-flat bottom 7-1/2" below the waterline. Thus I disposed of the deep, heavy, massively intricate keel structures of the Strange and Herreshoff designs. The result is a backyard project suitable for someone who has built a few strip-planked kayaks or dinghies. Dovekie's unorthodox flat rocker has wave-making habits that look and feel odd, but the boats are as fast as anything else in the same SA/D class. I guess as soon as you heel a bit, you've got some rocker...

|

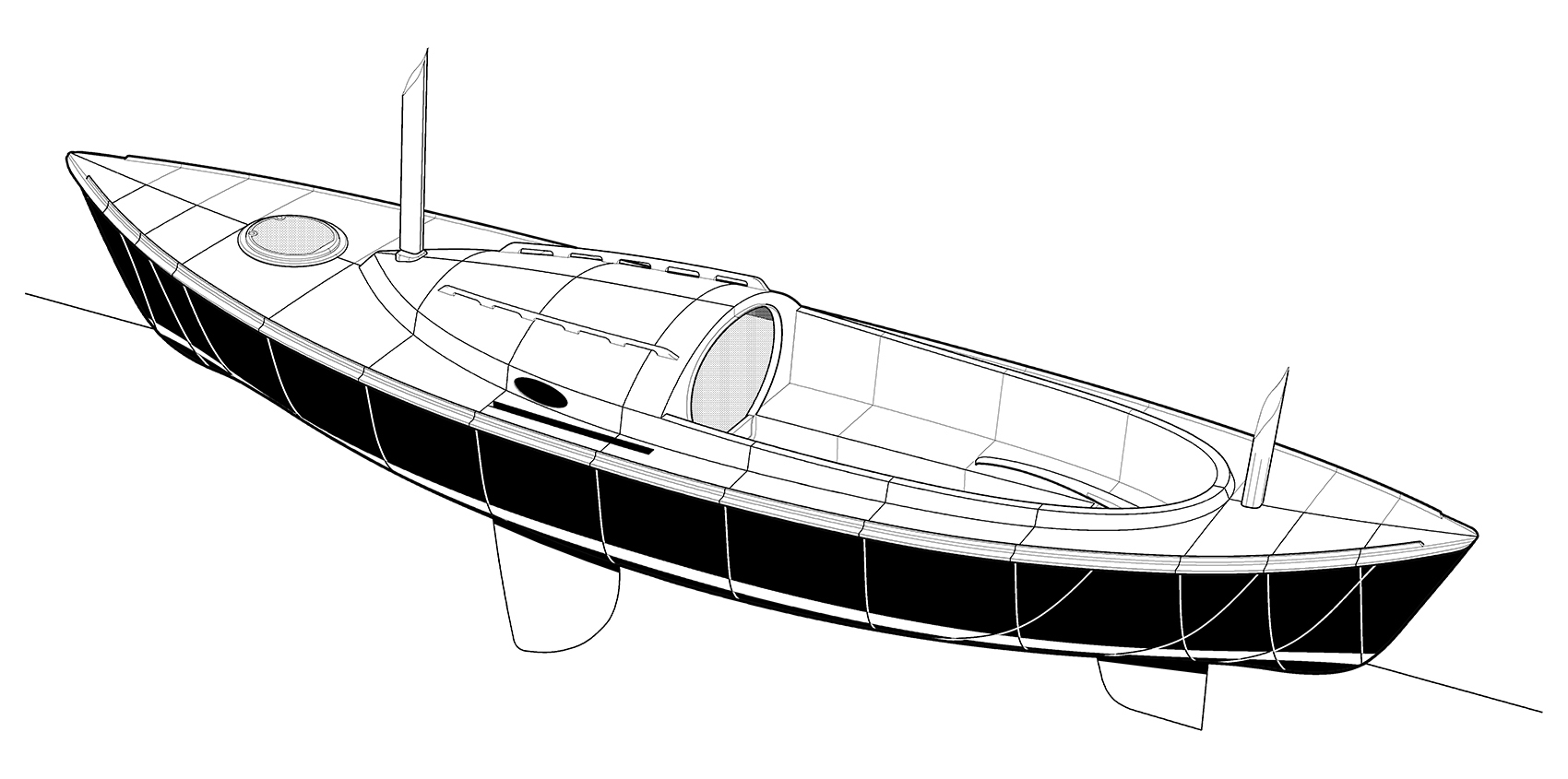

| This took a very, very long time to draw. Getting the stem and stern, sheerline, cabin trunk and coamings, and a bit of Herreshoffian hollow in the ends to work together is a mountain to climb. |

If I were trying to sell Ollie to the Annapolis Boatshow crowd, she could do with another foot or two of freeboard. This would result in a greater range of stability and an interior that was less "bivouac" and more "cabin." But it would also elevate the project into a tier of weight, complexity, and cost that I was trying to avoid, especially now that used sailboats (including Dovekies) cost less than the pile of materials required to build Ollie.

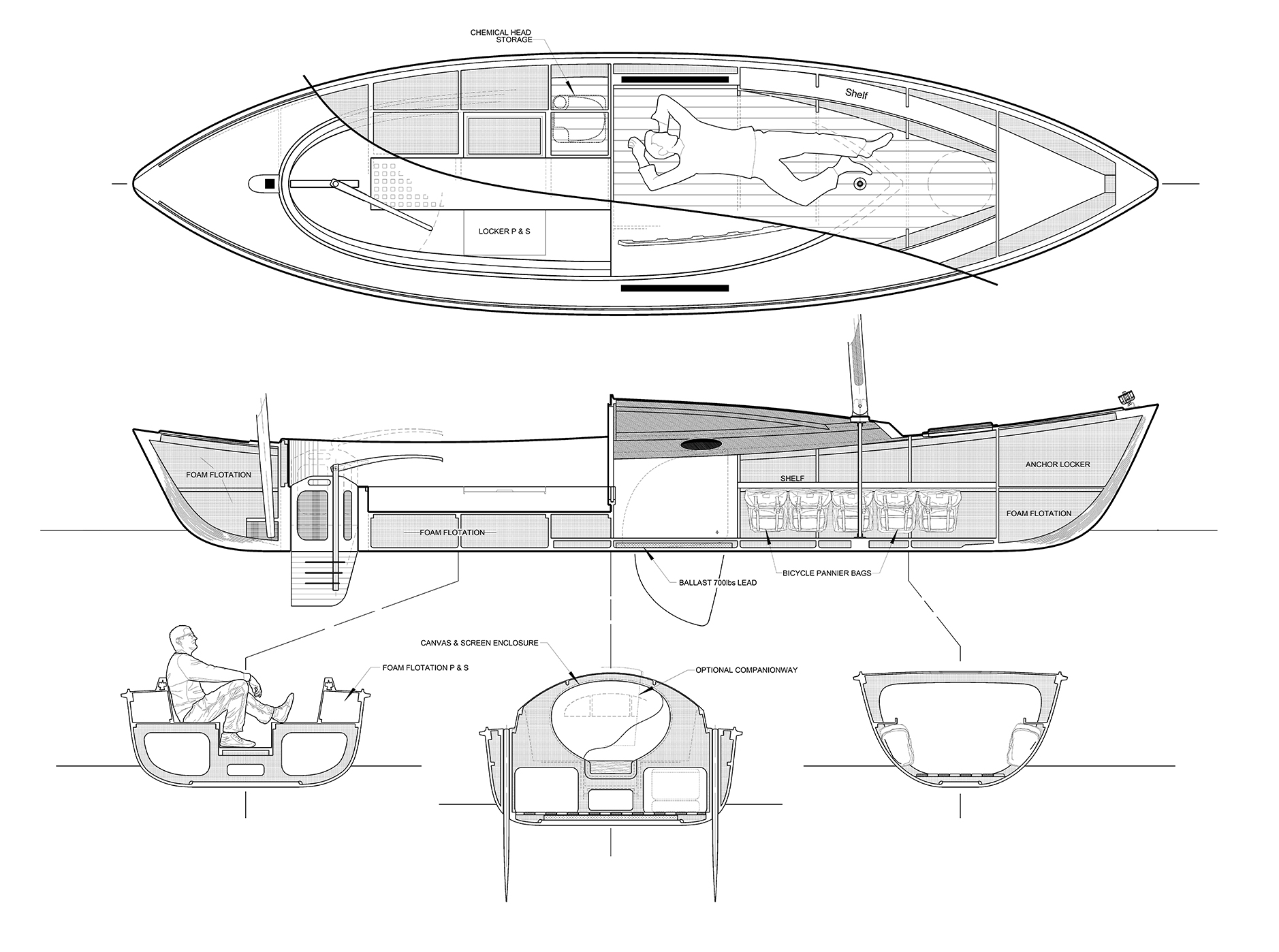

The bottom is two layers of 3/4" fir plywood, for strength and ballast. The sides are strip-planked in 3/4" cedar and sheathed inside and out with fiberglass along with the bottom panel. Deck and cockpit are 3/8" okoume plywood. The top of the sleek coach would have to be strip-planked. A mid-height stringer to stiffen the topsides is set into the molds before planking commences. The stringer supports cockpit seats and long, fiddled shelves outboard in the cabin. The shelves and oiled cedar floorboards comprise the entirety of the cabin furniture. With a couple of beanbags and a camp stove, I'd be content to wait out a 48-hour gale in that snug space. The 90-inch-long cockpit is available for sleeping, too.

As drawn the wide companionway is zipped up with a canvas door. For simplicity and weight savings there is no companionway slider atop the coach. Herreshoff tried this argument on his Rozinante builders, but most opted for a slider, and a more dignified entry and egress. I expect the conventional companionway shown in dotted lines would be more popular among Ollie builders.

|

| The cabin is an open "romper room." It has sitting headroom and would be a cozy place to retreat on a stormy night at anchor. You might add a small locker or two and a folding shelf for a stove, but this boat is MUCH smaller than it looks on paper. Settees, saloon tables, and so on will make the interior FEEL small, too. |

|

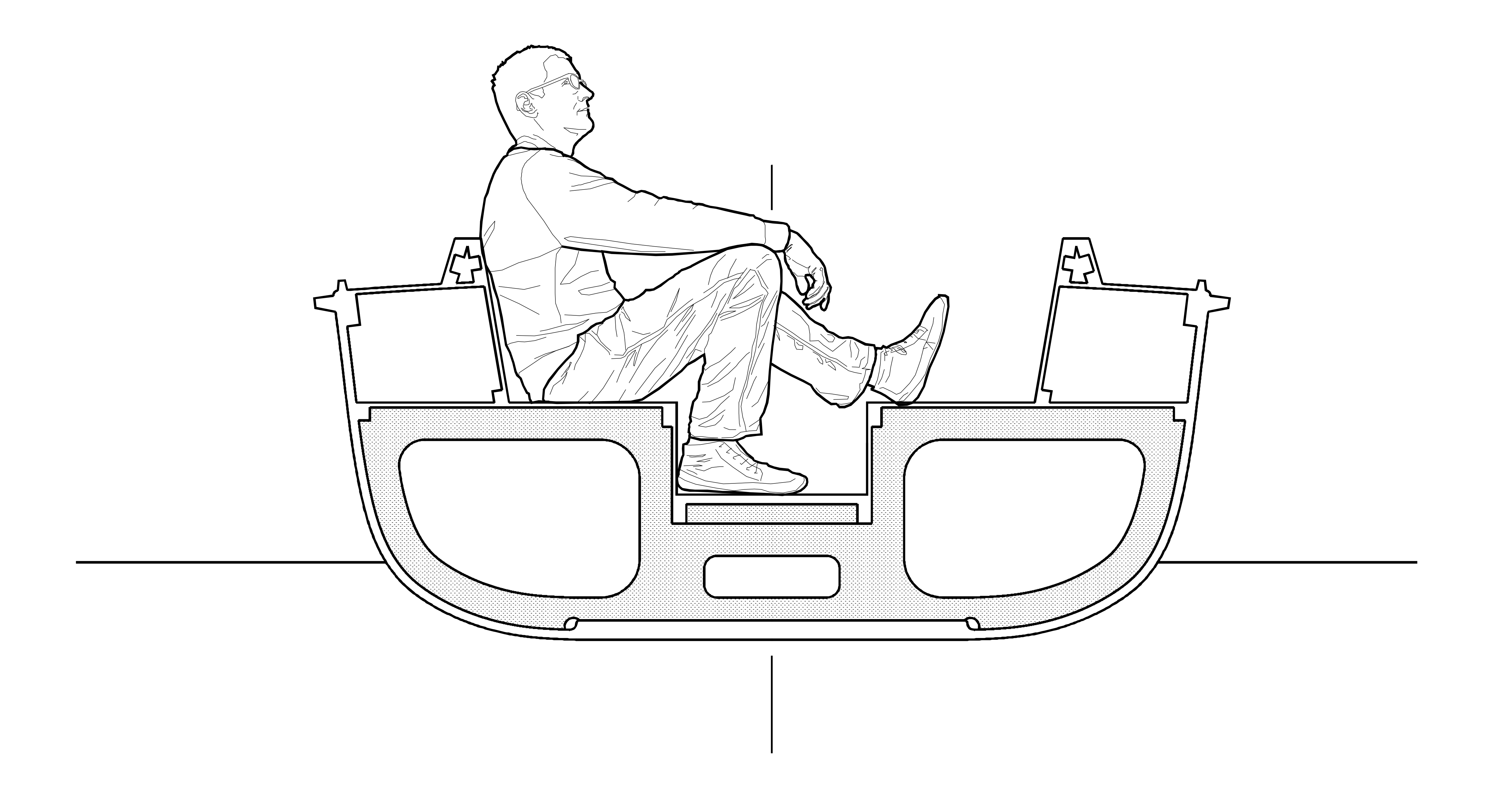

| I mocked up the cockpit with scrap plywood in the shop at CLC. Yachties who have spent more time studying drawings than sailing will be irritated by what they perceive as a footwell that is too narrow and shallow. However, the seat edge is positioned exactly where you'll brace with your feet as the boat begins to heel. People...listen! You do not sit in sailboat cockpits the way you sit in church pews. |

Beneath the floorboards amidships resides a 700 pound slab of lead ballast, equivalent to the weight of an empty Dovekie. Ollie will stand up to more sail, and the safety margins are greater if overtaken by a squall. (The mainmast should be very light, ideally scavenged from a decommissioned racing dinghy.)

The narrow, shallow hull will be fast, and between the ballast and her hard bilges, she'll tend to sail upright. With prudence and the many sail-shortening options afforded by the split rig, modest crossings and coastwise adventures are of no concern to a decent boatman. I'd rather make the crossing to the Bahamas in Ollie than in a lot of boats that have done it, including some heavier ones. The only thing I would change for over-the-horizon adventures is to make the companionway higher and narrower.

Ollie is more or less a big, decked-in skiff, and is not going to be self-righting like a keelboat. Max stability peaks early, at 30 degrees. At 45 degrees the crew had better let the sheets fly. Dovekies can and do capsize if handled incompetently; Ollie could, too, in theory. The foam-cored Dovekie floats but is a mess to recover once swamped. The free-surface effect of water in her open interior will frustrate efforts to right her. Of the two I'd rather capsize Ollie. Pull the pins on the mainmast shrouds and Ollie should turn the right way up, her strategically-placed foam flotation working with the lead ballast to provide flooded stability. (Ollie is an obvious candidate for water ballast, but after some unhappy experiences, I have grown to dislike water ballast. In a capsized and swamped boat, the water ballast becomes neutral weight, offering no righting moment.)

|

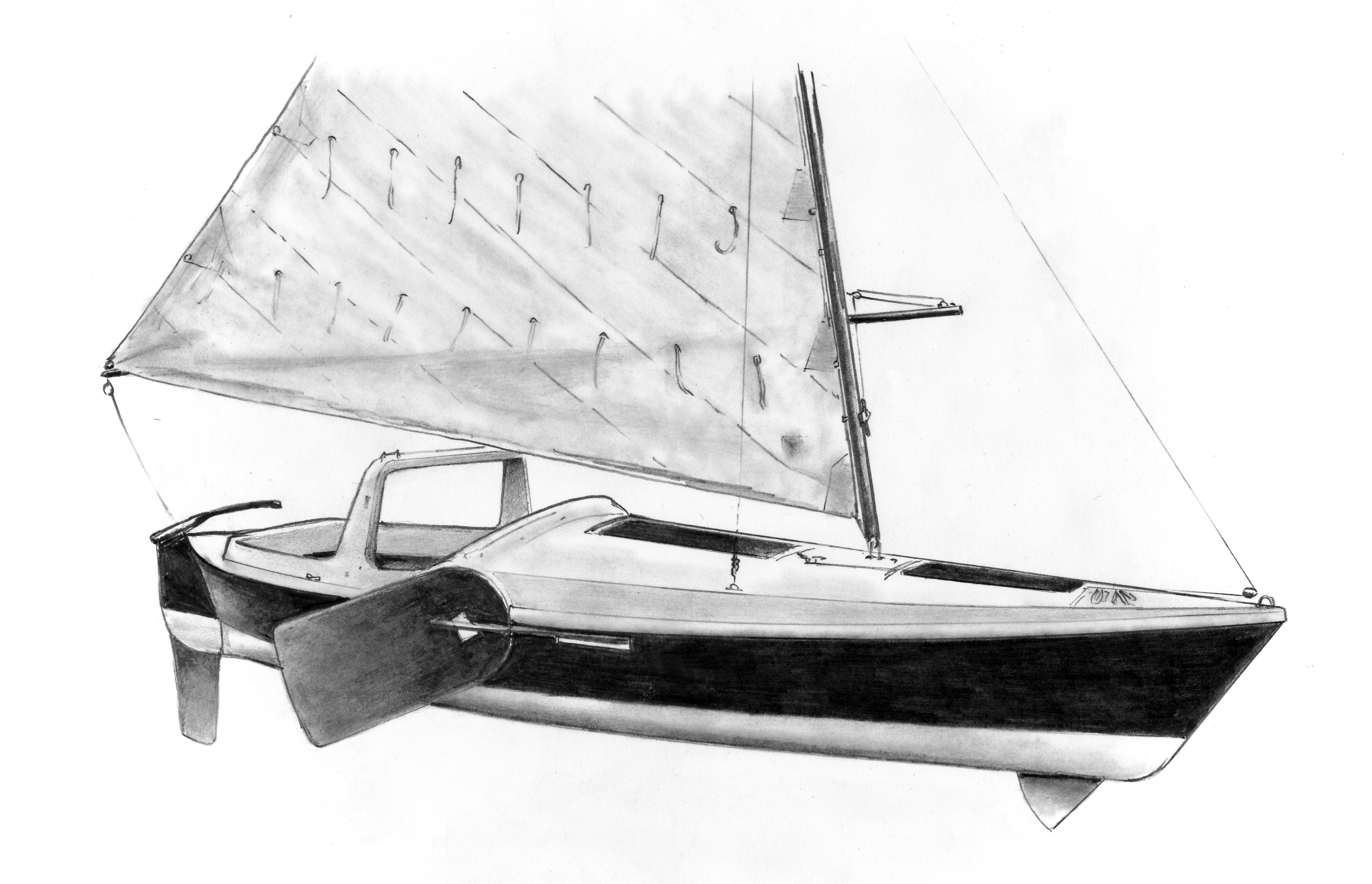

| All sailing nerds will note that the sailplan is a nod to Francis Herreshoff's Rozinante. |

I've owned many boats with leeboards and they haven't grown on me, especially not the big ones. You can engineer leeboards so that the windward board can be left down for short-tacking, but the mounts for such cantilevered leeboards have to be massively strong. Dovekie has that arrangement, and I've built a few boats with cantilevered leeboards. It puts a lot of weight up high, and building the mounts is more work than building two bilge board trunks.

I experimented with a pair of daggerboards amidships. Compared to the pivoting bilge boards, the builder would be spared several days of construction. The apertures in the hull would be smaller, and you might save a hundred pounds.

I switched to the pivoting boards because I anticipated a hailstorm of abuse from the armchair shoal-draft absolutists. Why, they would ask, would you go to the trouble to build such a shallow hull, only to saddle it with a fixed sailing draft? I don't buy the "must sail to windward in 10 inches of water" conceit that people get so wound up about. No one is going to sail for more than a few minutes in 29 inches of water. When it gets that shallow, you're either about to beach the boat for lunch, or you're skimming over a bar on the way to deeper water. Or about to be holed by a coral head or an old engine block mooring.

|

| Two pivoting bilge boards and a trunk-rudder. The elliptical cockpit is entirely for looks. It's not the hardest thing in the boat to build, but it's the hardest thing to illustrate in the plans for the builders... Basically, you build a very normal deck--no big deal--and saber-saw the shape of that cockpit ellipse into it. Then you set up little trapezoidal molds around the cockpit perimeter to define the shape, and plank it in. I would use vertical staving for the aft third of the cockpit coaming assembly. |

The final drawings show pivoting bilge boards drawing just under 30 inches. They are on the small side, and based on user experiences with similar lateral plane geometry in Autumn Leaves, you might often sail with both boards only partway down. The boards and the trunk openings are located in the turn of the bilge, a nasty position in terms of fluid dynamics. No worse than leeboards, I'd argue. I'd make mine out of thin aluminum plate so that the trunk openings could be as narrow as possible. At least the bilge board slots are immune to jamming with sand after a grounding.

Vocal and energetic criticism will be directed at the trunk-rudder. The objections are (again) the fixed sailing draft of such rudders (only 23"), the perceived complexity of construction, and the fear of jamming or breakage. I've built six or eight of these rudders and they are no harder to assemble than a typical centerboard trunk. The thick-walled 1-1/2" OD stainless pipe for the rudder shaft is available all over the internet. If you can strip-plank this hull, you can knock out one of these rudders.

The only thing that breaks is the bolt that attaches the tiller to the rudder post. It should be a stronger grade of stainless steel, and fitted with a bushing so that the bolt doesn't fail in shear where it passes through the tubular rudder shaft.

For your trouble, you get a rudder that's noticeably more efficient than the stern-hung variety. The skipper need not move more than a few inches to retract the rudder. And, while subjective, I do love the look of a clean stern in boats like this!

Use a long oar pivoting off the aft starboard quarter to steer when you cross that shallow bar or approach a beach.

I've declined to show any detail for auxiliary power. My best sailing memories are from the years I sailed an engineless Folkboat around the Chesapeake. Ollie is best served by a single sculling oar, about 10 feet long. It will stow below. You can make a knot or a knot-and-a-half in a calm. Engineless navigation requires old-fashioned patience and an open-ended schedule, which is why 19 out of 20 Ollies will have some sort of engine, probably slung off the stern quarter. A 2.5hp 4-stroke outboard will give you 4 or 4-1/2 knots in a calm. In 2022, there are many interesting electric options. I'm imagining some sort of retractable pod containing an electric motor.

Plans for Ollie, modulated for people familiar with building from plans, will be along soon.

return to section:

return to section: