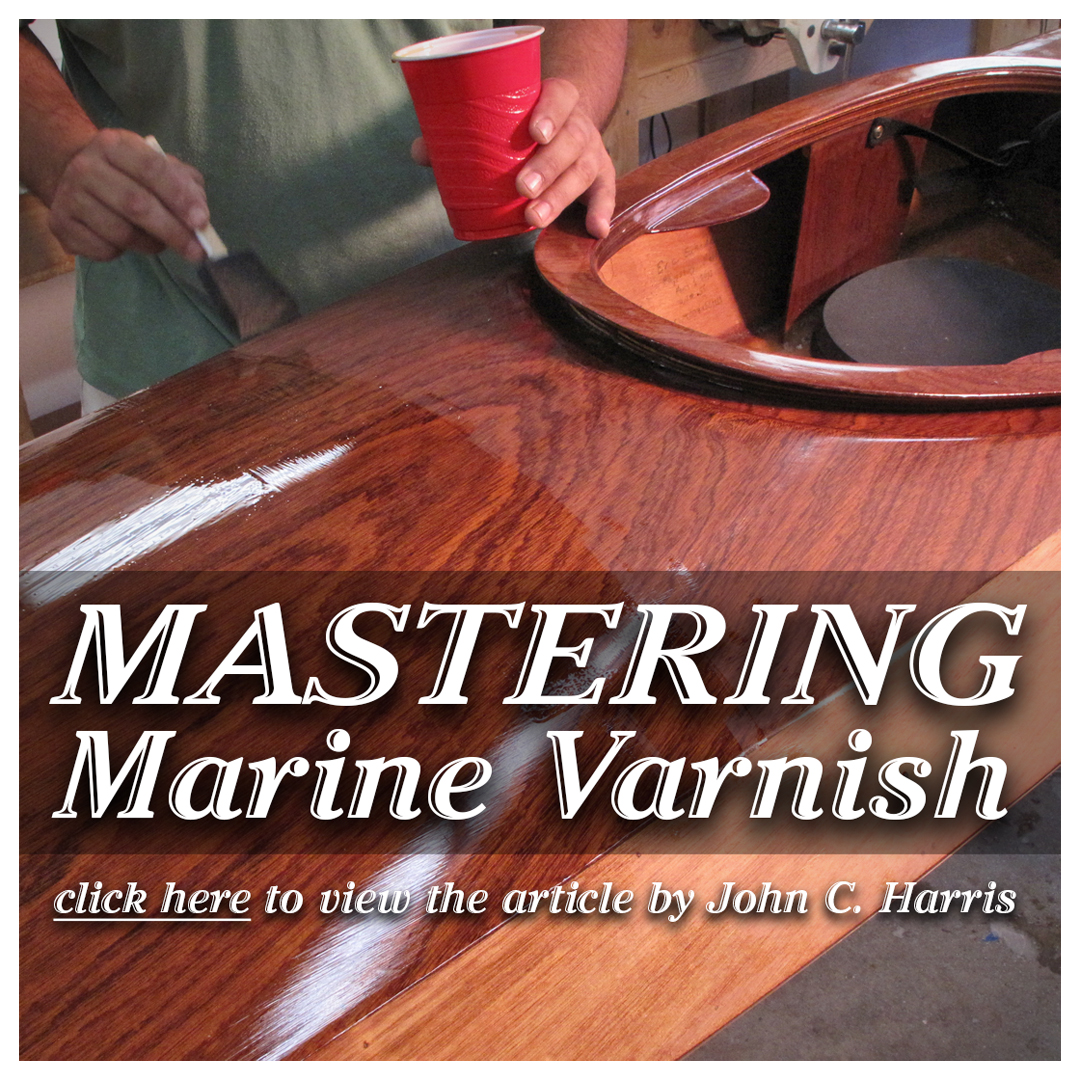

By John C. Harris

October 2010

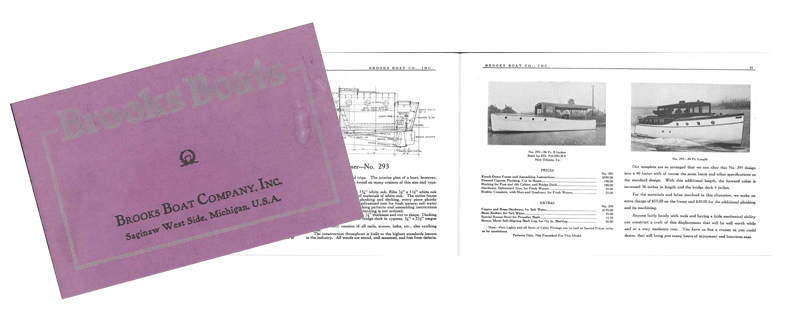

On my desk in front of me is a copy of the Brooks Boat Company, Inc. catalog for 1930.

|

| Brooks Boat Company, Inc. catalog, 1930 |

Brooks, based in Saginaw, Michigan, sold boat kits through the mail. It’s a thick, beautiful catalog with black-and-white photos and snappy descriptions. Kits range from a 9-foot dinghy ($42.50 for the complete kit) to a handsome 40-foot cabin cruiser ($917.50, not including an engine).

Brooks is long gone, but the tradition of boat kits is ancient. 4300 years ago, the Pharoah Khufu was laid to rest with 1,224 pieces of a 143-foot boat, ready to be reassembled when he reached the afterlife.

The first boats built by Europeans in North America were likely built from kits shipped across the Atlantic. With the "sportsman" movement of the late 19th century came a demand for affordable pleasure boats for the middle class, and the first retail boat kits.

I've seen ads for build-your-own-boat kits in magazines from the 1890's. There has been "amateur" boatbuilding since Noah, but the idea of recreational amateur boatbuilding appeared only in the last decade or two of the 19th century. Amateur boatbuilding seems to have really taken hold during the Great Depression. Magazines like Popular Mechanics, Popular Science, and boating magazines like The Rudder and Yachting World appealed to boaters of straitened means with articles on how to build their own small boat. The yachting magazines, in particular, seemed to survive on a steady stream of articles and pamphlets for first-time boatbuilders, and in their margins we find ads for boat kit companies.

The First Big Advance: Plywood that was good for things besides the bottoms of drawers

|

| Popular Science, 1935 |

The Chris Craft kits were a big advance over the plank-on-frame Brooks Boat Company kits, but there was still a lot of tricky joinery. In the days before modern adhesives, you fastened the plywood panels to wooden frames with with screws and some soft putty to keep the water out. This worked until the putty dissolved, whereupon the boat would start leaking, and pretty soon the boat itself would dissolve. (Almost none of the 93,000 Chris Craft kit boats survive today, though unopened kit boxes dating to the 1950's sometimes turn up in the stratigraphy of old basements and barns.)

The Invention of Stitch-and-Glue

The next big advance was the invention of “stitch-and-glue” construction. Stitch-and-glue changed everything for amateur boatbuilders. In England, in the late 1950’s, a man named Ken Littledyke cut out some plywood panels, stitched the edges of the panels together with fishing line, and reinforced the seams with putty made from polyester resin. Polyester resin is what holds together most fiberglass boats, and Ken’s plywood kayak was just as stiff and strong as a fiberglass boat. Coated with fiberglass, it seemed to hold up as well as the solid fiberglass boats, too. His friend Jack Holt used the process of stitching plywood panels together—substituting ductile copper wire for fishing line—and then gluing the panels with strong adhesives for a new design called the Mirror Dinghy. Subsequently more than 70,000 Mirror Dinghies were built, and amateur boatbuilding has never been the same.

The Chris Craft kits relied on a fairly intricate framework of solid timber, to which a skin of plywood was fastened. The framing was no joke to cut and fit. There were curves and angles that could, and did, defeat a lot of amateur boatbuilders. Get the fits wrong and your plywood boat could leak like a colander. Stitch-and-glue boat designs require little (if any) framing, or any need for tight joinerwork. In stitch-and-glue boats, the plywood skin is itself a “monocoque” structure, reinforced with a fiberglass sheathing. If your plywood parts don’t fit perfectly, you simply trowel on more epoxy putty to close the gap, and get on with it.

Epoxy: We All Get Sticky

The third huge advance in amateur boatbuilding came in the form of epoxy adhesives and coatings, developed for aerospace applications in the 1960’s. Many times stronger than polyester resin and putty, epoxy allowed designers to create strong, lightweight, beautiful boats with even less traditional framing than before. If mixed correctly, epoxy will conceal grave sins of woodworking joinery: just get two pieces of wood in rough proximity to one another, fill the space between with plenty of epoxy, and you have a structure with strength properties rivaled only by steel---but much lighter. By the 1980’s, there were boat kits that contained not a single stick of solid wood: they were nothing but artfully cut sheets of plywood joined at their edges by epoxy, often as sculptural in appearance as they were functional on the water. Epoxy made it possible.

Computers for the People

The final major advance that benefits all amateur boatbuilders was the widespread adoption, in the 1990’s, of computers in the design of small boats, and the computer-aided manufacture of boat kits. All the ingredients were in place: lightweight, ultra-high-quality marine plywood; space-age epoxy adhesives to hold things together; and software and hardware that even boatbuilders could operate. Computers freed naval architects to create designs that were sophisticated, beautiful, and easier to build than anything that had come before.

Whereas boat designs intended for amateurs often LOOKED like something a tyro would build, the new generation of stitch-and-glue boat kits for first-time builders are as sleek and elegant as anything a professional could turn out. Assembly is closer and closer to a snap-together airplane model. Coated in fiberglass inside and out, modern boat kits can last forever with minimal maintenance.

This Whitehall-style kit boat, a Chester Yawl by CLC, was designed on a computer, cut out on a computer, and assembled by an amateur boatbuilder.

Computer-designed stitch-and-glue kayaks, like this Night Heron by Nick Schade, are easy to put together but as elegant as any boat design ever set to paper.

return to section:

return to section: